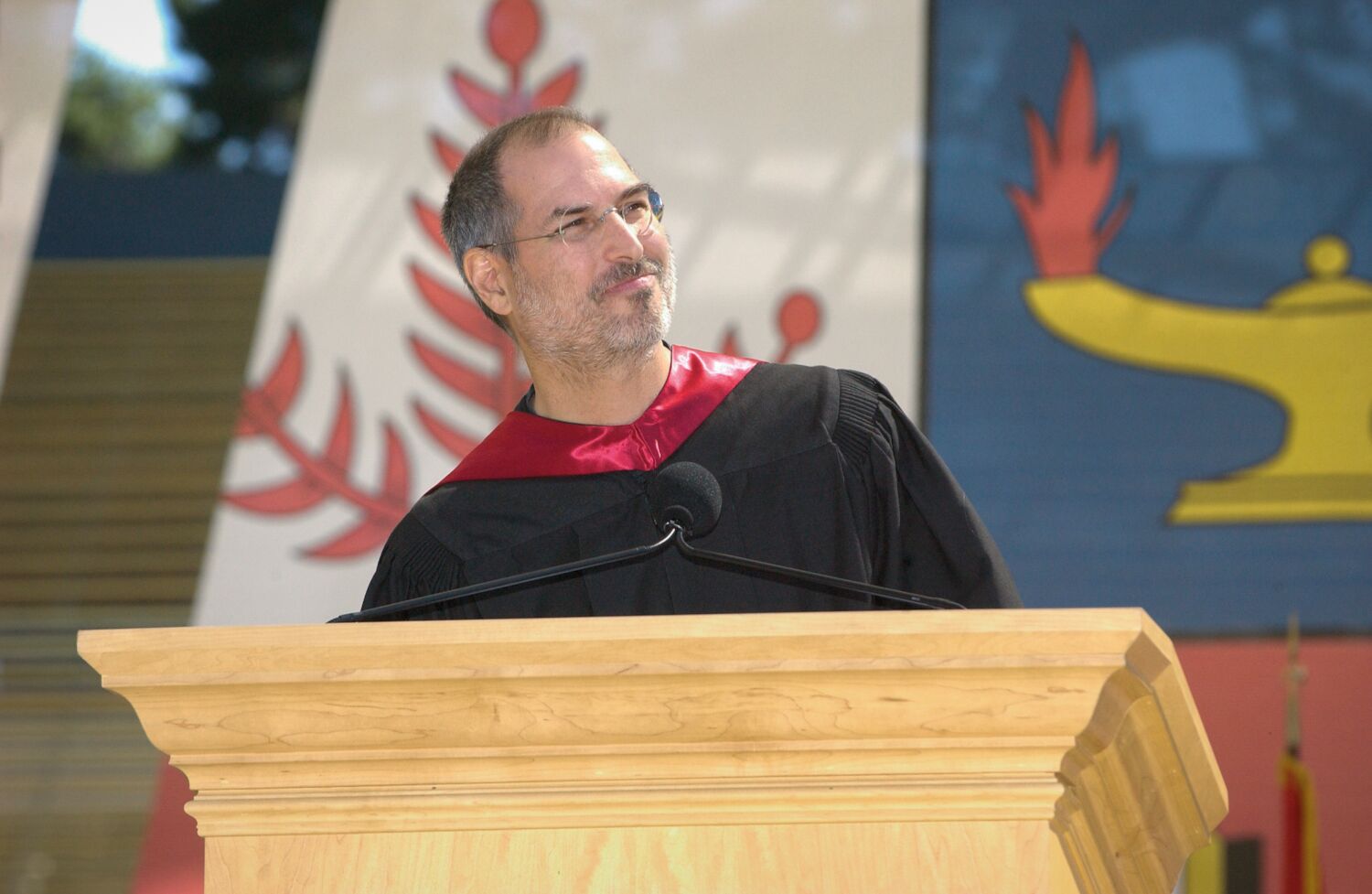

Make Something Wonderful

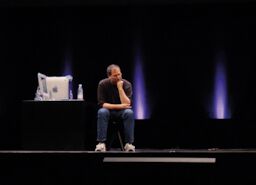

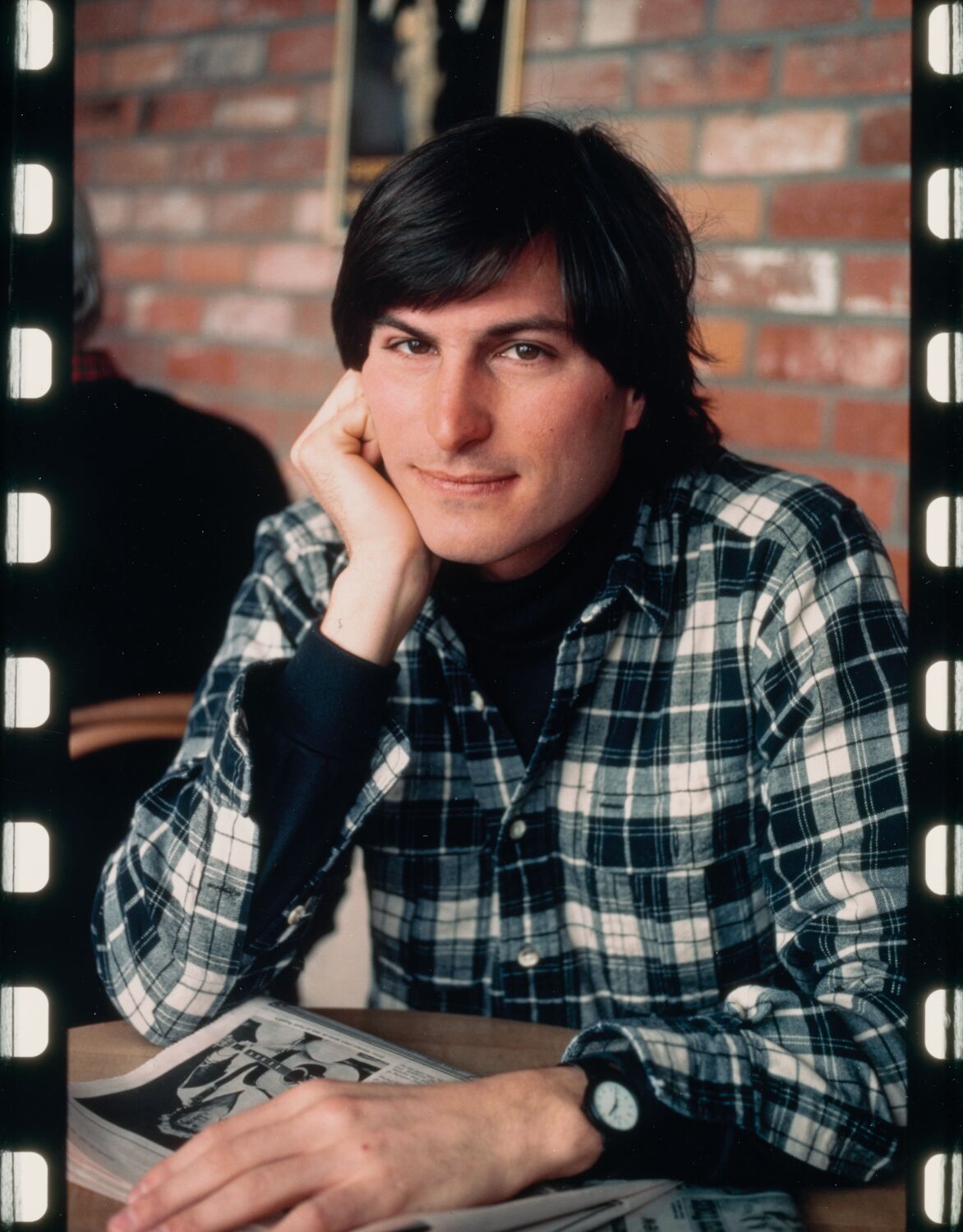

Steve Jobs in his own words

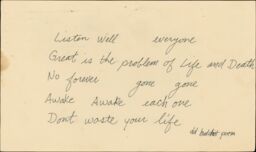

There’s lots of ways to be, as a person. And some people express their deep appreciation in different ways. But one of the ways that I believe people express their appreciation to the rest of humanity is to make something wonderful and put it out there.

And you never meet the people. You never shake their hands. You never hear their story or tell yours. But somehow, in the act of making something with a great deal of care and love, something’s transmitted there. And it’s a way of expressing to the rest of our species our deep appreciation. So we need to be true to who we are and remember what’s really important to us.

—Steve, 2007

Introduction by

Laurene Powell Jobs

The best way to understand a person is to listen to that person directly. And the best way to understand Steve is to listen to what he said and wrote over the course of his life. His words—in speeches, interviews, and emails—offer a window into how he thought. And he was an exquisite thinker.

Much of what’s in these pages reflects guiding themes of Steve’s life: his sense of the worlds that would emerge from marrying the arts and technology; his unbelievable rigor, which he imposed first and most strenuously on himself; his tenacity in pursuit of assembling and leading great teams; and perhaps, above all, his insights into what it means to be human.

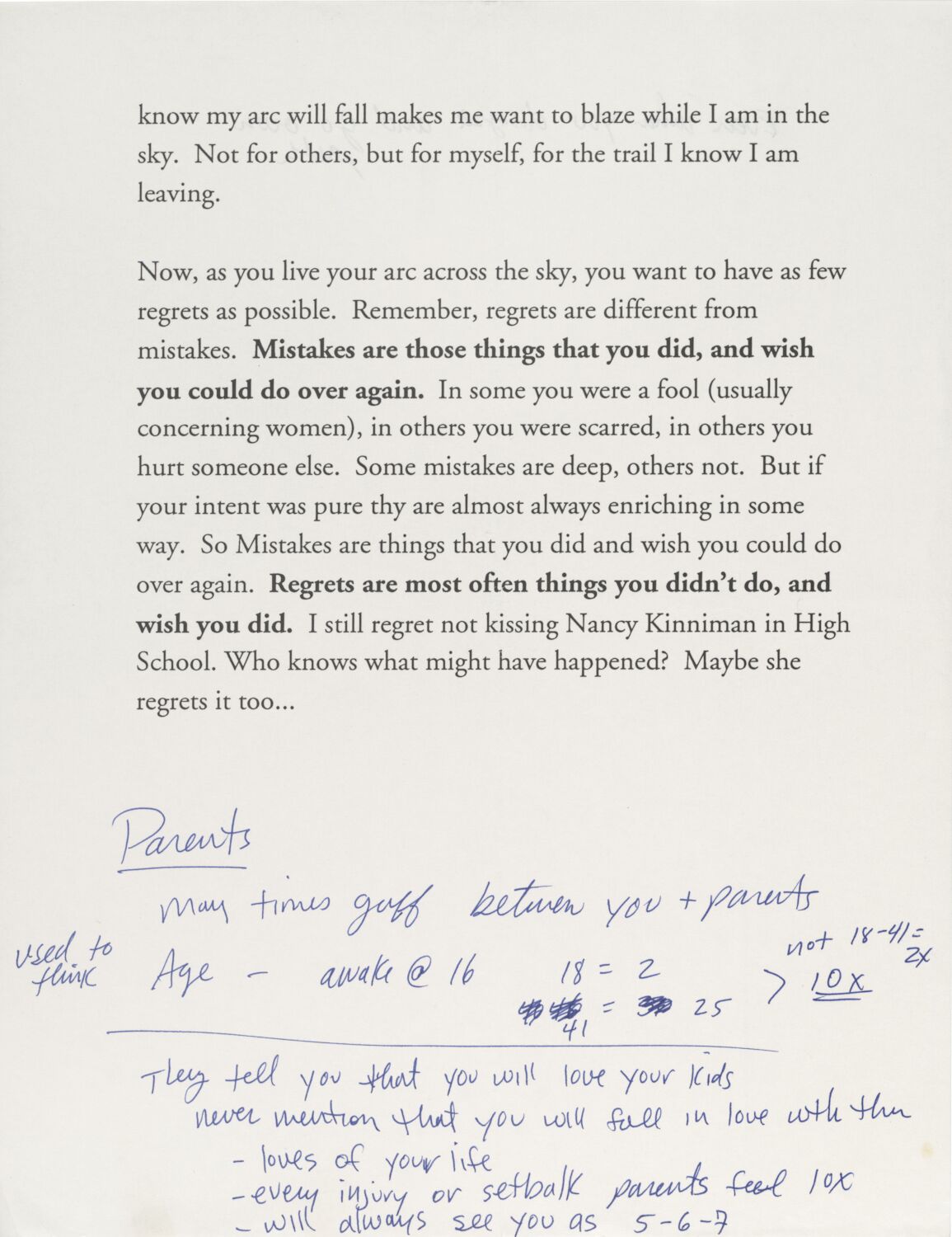

Steve once told a group of students, “You appear, have a chance to blaze in the sky, then you disappear.” He gave an extraordinary amount of thought to how best to use our fleeting time. He was compelled by the notion of being part of the arc of human existence, animated by the thought that he—or that any of us—might elevate or expedite human progress.

It is hard enough to see what is already there, to gain a clear view. Steve’s gift was greater still: he saw clearly what was not there, what could be there, what had to be there. His mind was never a captive of reality. Quite the contrary: he imagined what reality lacked and set out to remedy it. His ideas were not arguments, but intuitions, born of a true inner freedom and an epic sense of possibility.

In these pages, Steve drafts and refines. He stumbles, grows, and changes. But always, always, he retains that sense of possibility. I hope these selections ignite in you the understanding that drove him: that everything that makes up what we call life was made by people no smarter, no more capable, than we are; that our world is not fixed—and so we can change it for the better.

Edited by Leslie Berlin

Published by the Steve Jobs Archive

Contents have been edited and excerpted for clarity and privacy.

✂ indicates that several sentences or paragraphs have been removed from the original.

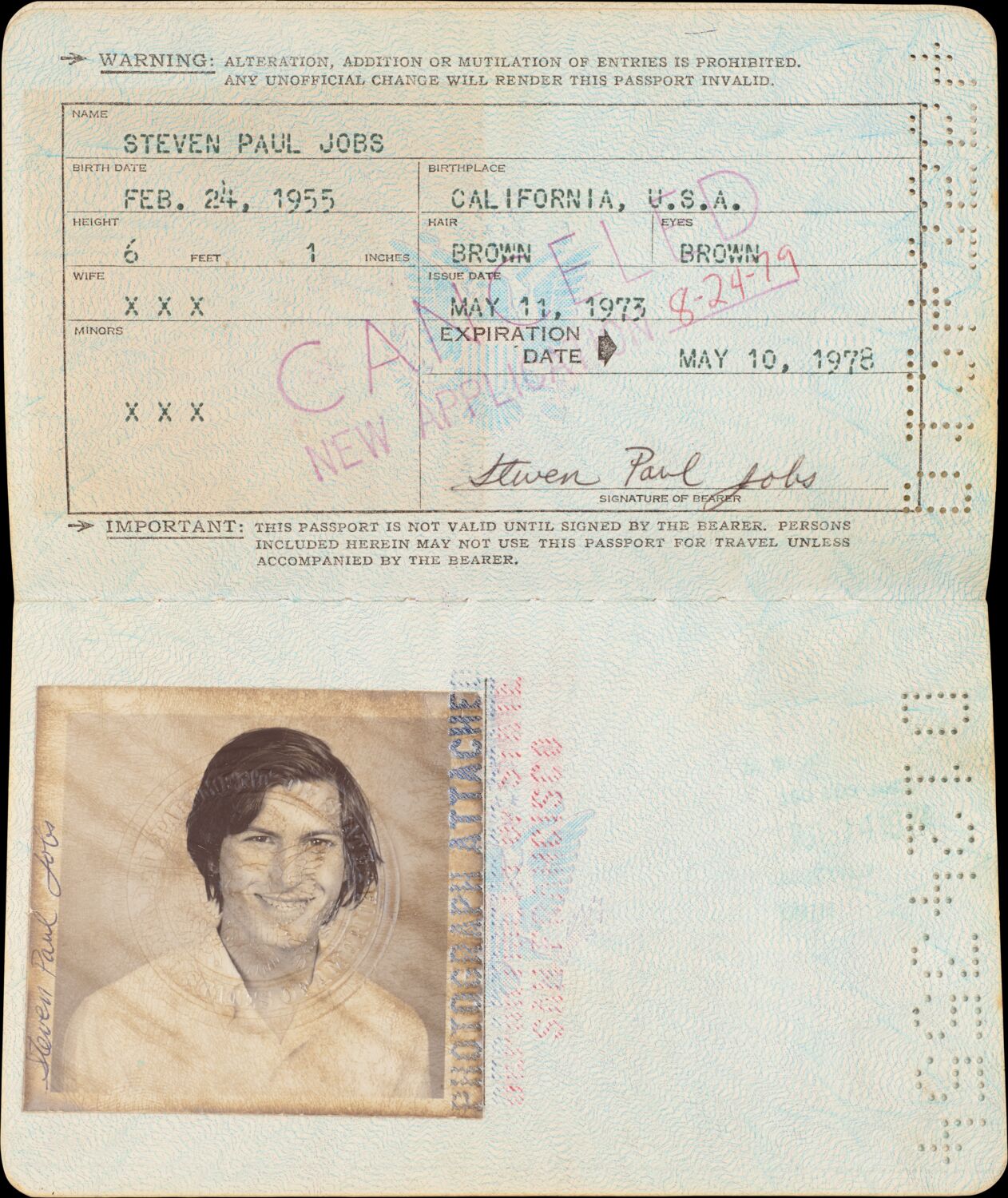

Preface: Steve on His Childhood and Young Adulthood

Steve typically kept his personal life private, but he did occasionally talk about growing up in the San Francisco Bay Area. It was a time when engineers and programmers began flooding into what came to be known as Silicon Valley.

In 1995, he recorded an oral history for the Smithsonian.

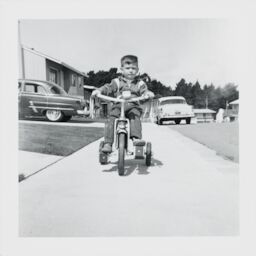

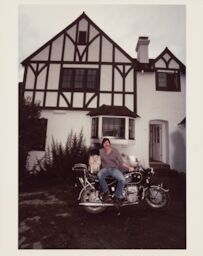

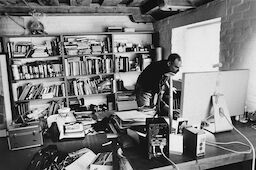

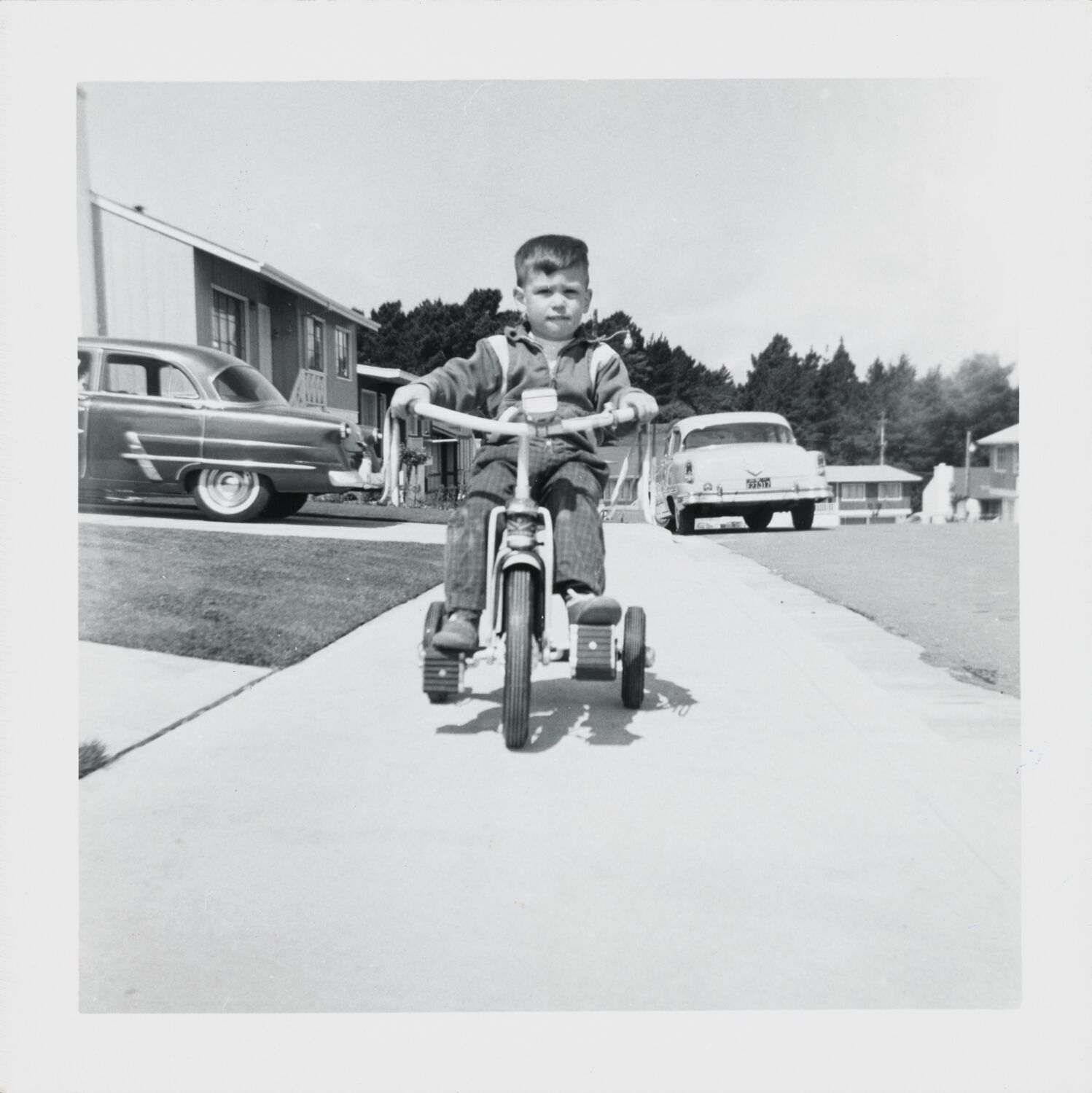

I was very lucky. I had a father, named Paul, who was a pretty remarkable man. He never graduated from high school. He joined the Coast Guard in World War II and ferried troops around the world for General Patton, and I think he was always getting into trouble and getting busted down to Private. He was a machinist by trade and worked very hard and was kind of a genius with his hands.

He had a workbench out in the garage where, when I was about five or six, he sectioned off a little piece of it and said, “Steve, this is your workbench now.” And he gave me some of his smaller tools and showed me how to use a hammer and saw and how to build things. It really was very good for me. He spent a lot of time with me, teaching me how to build things, take things apart, put things back together.

One of the things that he touched upon was electronics. He did not have a deep understanding of electronics himself, but he’d encountered electronics a lot in automobiles and other things that he would fix. He showed me the rudiments of electronics, and I got very interested in that.

I grew up in Silicon Valley. My parents moved from San Francisco to Mountain View when I was five. My dad got transferred, and that was right in the heart of Silicon Valley, so there were engineers all around. Silicon Valley, for the most part, at that time, was still orchards—apricot orchards and prune orchards—and it was really paradise. I remember almost every day the air being crystal clear, where you could see from one end of the valley to the other. It was really the most wonderful place in the world to grow up.

There was a man that moved in down the street, maybe about six or seven houses down the block, who was new in the neighborhood with his wife. And it turned out that he was an engineer at Hewlett-Packard and he was a ham-radio operator and really into electronics. What he did to get to know the kids on the block was rather a strange thing: he put out a carbon microphone and a battery and a speaker on his driveway, where you could talk into the microphone and your voice would be amplified by the speaker. Kind of a strange thing when you move into a neighborhood, but that’s what he did. ✂

I got to know this man, whose name was Larry Lang, and he taught me a lot of electronics. He was great. He used to build Heathkits. Heathkits were really great. Heathkits were these products that you would buy in kit form. You actually paid more money for them than if you just went and bought the finished product, if it was available. These Heathkits would come with these detailed manuals about how to put this thing together, and all the parts would be laid out in a certain way and color coded. You’d actually build this thing yourself.

I would say that gave one several things. It gave one an understanding of what was inside a finished product and how it worked, because it would include a theory of operation. But maybe even more importantly, it gave one the sense that one could build the things that one saw around oneself in the universe. These things were not mysteries anymore. I mean, you looked at a television set, and you would think, “I haven’t built one of those—but I could. There’s one of those in the Heathkit catalog, and I’ve built two other Heathkits, so I could build a television set.” Things became much more clear that they were the results of human creation, not these magical things that just appeared in one’s environment that one had no knowledge of their interiors. It gave a tremendous degree of self-confidence that, through exploration and learning, one could understand seemingly very complex things in one’s environment. My childhood was very fortunate in that way. ✂

School was pretty hard for me at the beginning. My mother taught me how to read before I got to school, and so when I got there I really just wanted to do two things: I wanted to read books, because I loved reading books, and I wanted to go outside and chase butterflies. You know, do the things that five-year-olds like to do. I encountered authority of a different kind than I had ever encountered before, and I did not like it. And they really almost got me. They came this close to really beating any curiosity out of me.

By the time I was in third grade, I had a good buddy of mine, Rick Ferrentino, and the only way we had fun was to create mischief. I remember there was a big bike rack where everybody put their bikes, maybe a hundred bikes in this rack—and we traded everybody our lock combinations for theirs on an individual basis. Then [we] went out one day and put everybody’s lock on everybody else’s bike, and it took them until about ten o’clock that night to get all the bikes sorted out. We set off explosives in teachers’ desks. We got kicked out of school a lot.

In fourth grade I encountered one of the other saints of my life. They were going to put me and Rick Ferrentino into the same fourth-grade class, and the principal said at the last minute, “No, bad idea. Separate them.” So this teacher, Mrs. Hill, said, “I’ll take one of them.” She taught the advanced fourth-grade class, and thank God I was the random one that got put in the class. She watched me for about two weeks and then approached me. She said, “Steven, I’ll tell you what. I’ll make you a deal. I have this math workbook, and if you take it home and finish it on your own without any help, and you bring it back to me, if you get it 80 percent right, I will give you five dollars and one of these really big suckers.” She [had] bought [a sucker], and she held it out in front of me—one of these giant things.

And I looked at her like, “Are you crazy, lady? Nobody’s ever done this before!” And of course I did it. She basically bribed me back into learning, with candy and money. And what was really remarkable was before very long I had such a respect for her that it sort of reignited my desire to learn. She was remarkable. She got me kits for making cameras. I ground my own lens and made a camera. It was really quite wonderful. I think I probably learned more academically in that one year than I’d ever learned in my life.

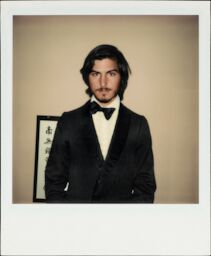

In 1984, Steve chatted with reporter David Sheff about how, as young adults, he and others of his generation began to develop their own cultural outlook.

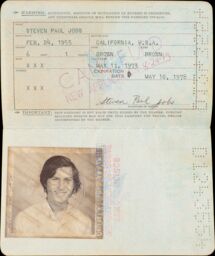

My parents never pushed me to go to college, but they always wanted to make sure that if I wanted to go, they had the resources to do it. And they saved, they really sacrificed some and saved some money up [for me to attend Reed College], but […] after six months, it just, it just seemed really absurd to be spending their life savings putting me through college.

I didn’t know enough about what I wanted to do, and besides that, I figured I could drop out and then drop back in and take the classes anyway and learn just as much. So I dropped out after six months, and then I dropped in for a little over a year.

I spent about a year and a half there, maybe close to two years. And I enjoyed it greatly. It was a hard time in my life, but I enjoyed it a lot. I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life. And Reed was a very intense place, very bright people—everyone out to change the world, but not knowing quite how. ✂

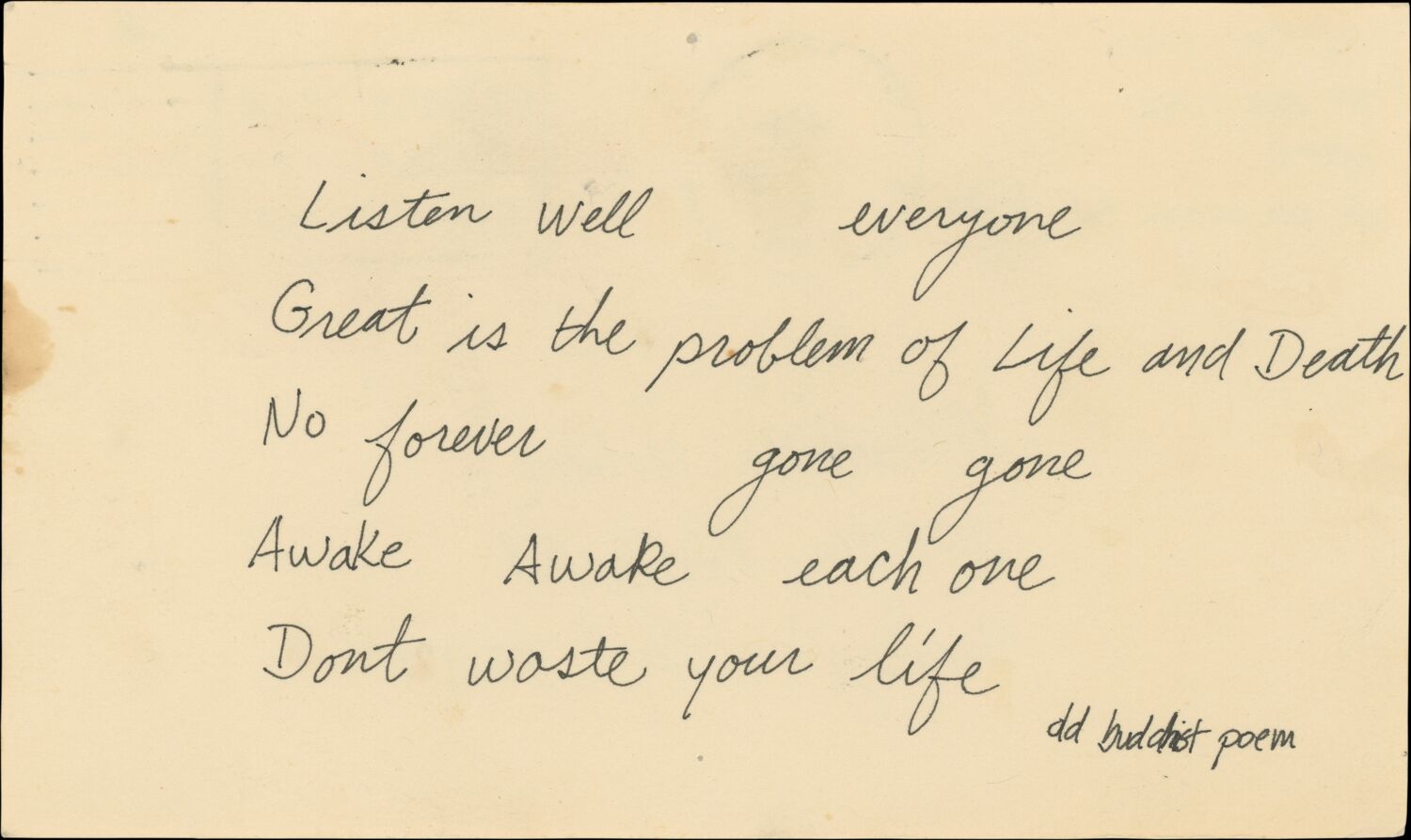

The early seventies was the time that sort of Eastern mysticism hit the shores of the United States. And we had a constant flow of people traveling through Reed, stopping off at Reed. Everyone from Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert to Gary Snyder, people like that. So there’s a constant flow of intellectual questioning about the truth of life and existence. ✂

The idealistic wind of the sixties was still at our back, and most of the people that I know that are my age have that ingrained in them forever. They have that idealism in them, but they also have a certain cautiousness about sort of ending up working in a natural food store behind the counter when they’re forty-five years old, which is what they saw some of their older friends [doing]—not that that’s bad in and of itself, but it’s bad if that’s not what you really set out to do or what you really wanted to be doing.

So that idealism was formed, but also the feeling that there had to be a more successful way [of] realizing some of that idealism.

Steve also recalled his time in California and India after leaving Reed College.

I came back down [to the San Francisco Bay Area] ’cause I decided I wanted to travel, but I was lacking the necessary funds.

This was California. You can get LSD fresh-made from Stanford University. You can go sleep on the beach at night with your girlfriends and whatever meaningful others. You could … I didn’t really realize how different California was than the middle of America, and even to some extent the East Coast, until I traveled to those places. I’d never been to any of those places until my early twenties. California has a sense of experimentation about it, and a sense of openness about it—openness and new possibility—that I really didn’t appreciate till I went to other places.

So I came back down to get a job, and I was looking in the paper and there was this ad that […] talked about being an engineer and having fun at the same time. It sounded like fun, so I called. It was [video game manufacturer] Atari. And I filled out an application, just listed all the things that I’d done, and the personnel woman said, “Well, don’t call us, we’ll call you!” But then some stroke of luck got my application to a man named Al Alcorn, who was the vice president of engineering at Atari at the time. And he called me up the next day and hired me, and it was great. […] I was there a little less than a year, and they had shipped a bunch of games to Europe that had some engineering defects in them. I figured out how to fix them, but it was necessary for somebody to go over there and actually do the fixing.

So I volunteered to go; well, they asked me if I’d go, and I said I definitely would love to, but I’d like to take a leave of absence when I was there. So they let me do that, and I ended up in Switzerland and flew from Zurich to New Delhi. And I spent some time in India.

I’m stupefied to sort of summarize [my trip to India]. Anyone would have a hard time summarizing a meaningful experience of their life in a page. I mean, if I was William Faulkner, I might be able to do it for you, but I’m not.

Coming back was more of a culture shock than going. All I really wanted to do [after returning to California] was to go find a grassy meadow and just sit. I didn’t want to drive a car. I didn’t want to go to San Francisco or do all these things. I didn’t want to do it.

So I didn’t, for about three months. I just read and sat. When you are a stranger in a place, you notice things that you rapidly stop noticing when you become familiar. I was a stranger in America for the first time in my life, and so I saw things I’d never seen before. And I tried to pay attention to them for those three months because I knew that gradually, bit by bit, my familiarity would be gained again.

Part I, 1976–1985

“A lot of people put a lot of love into these products.”

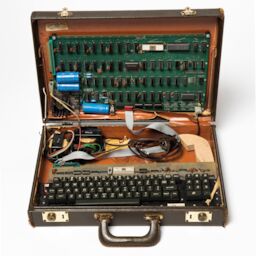

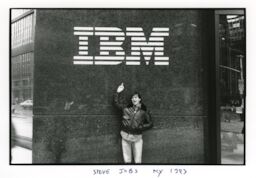

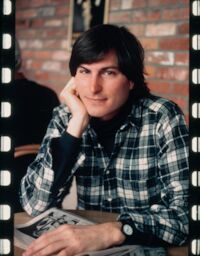

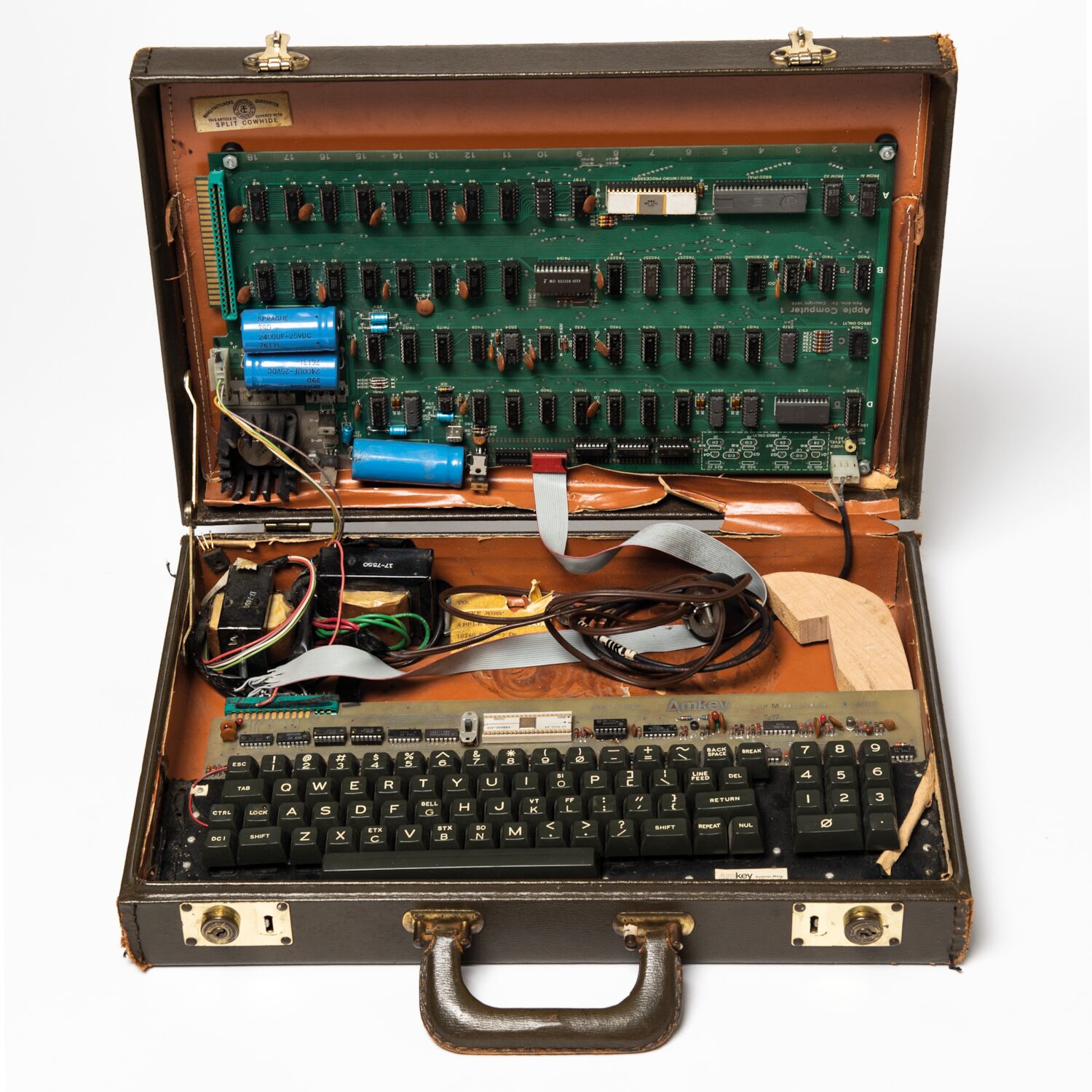

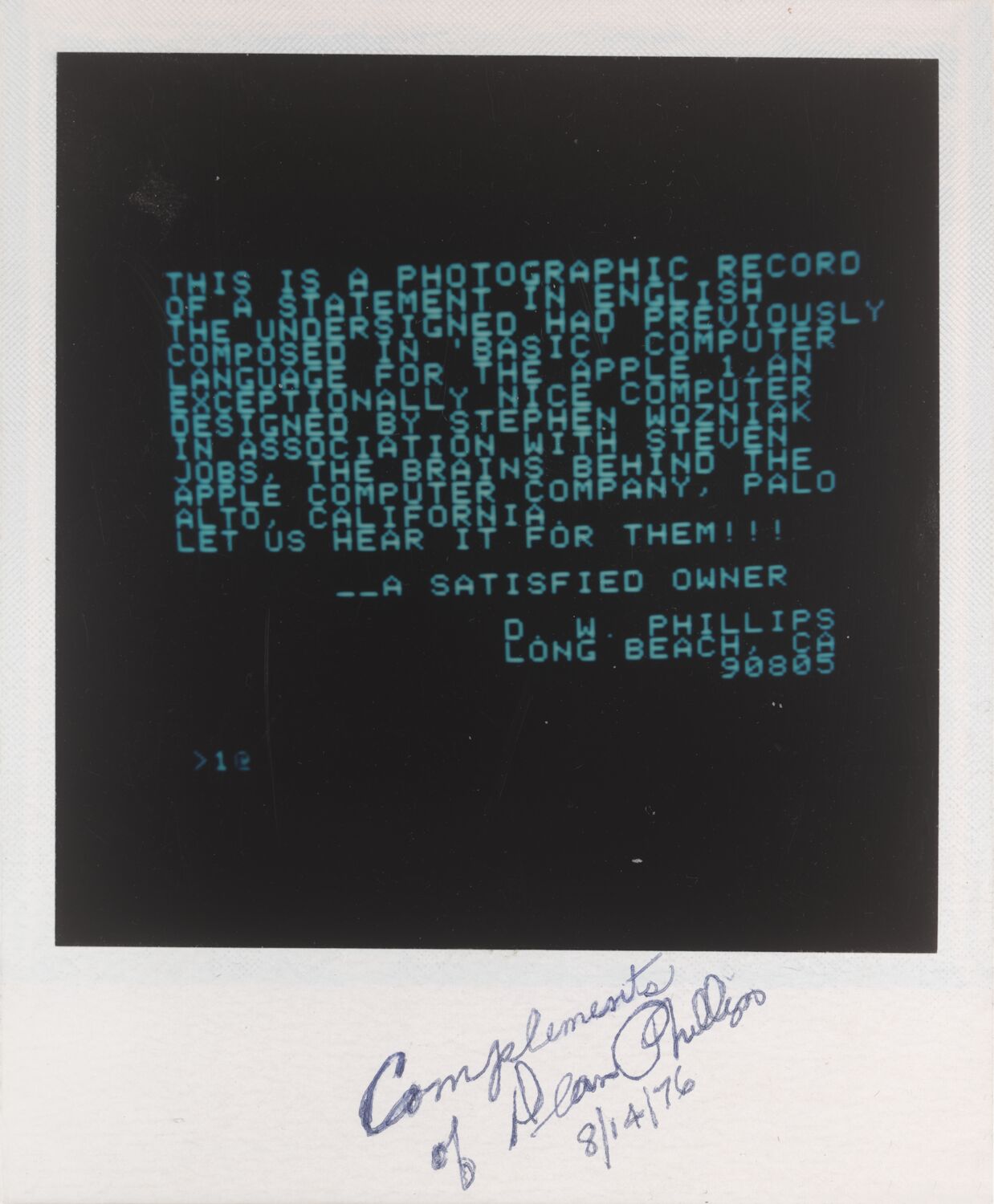

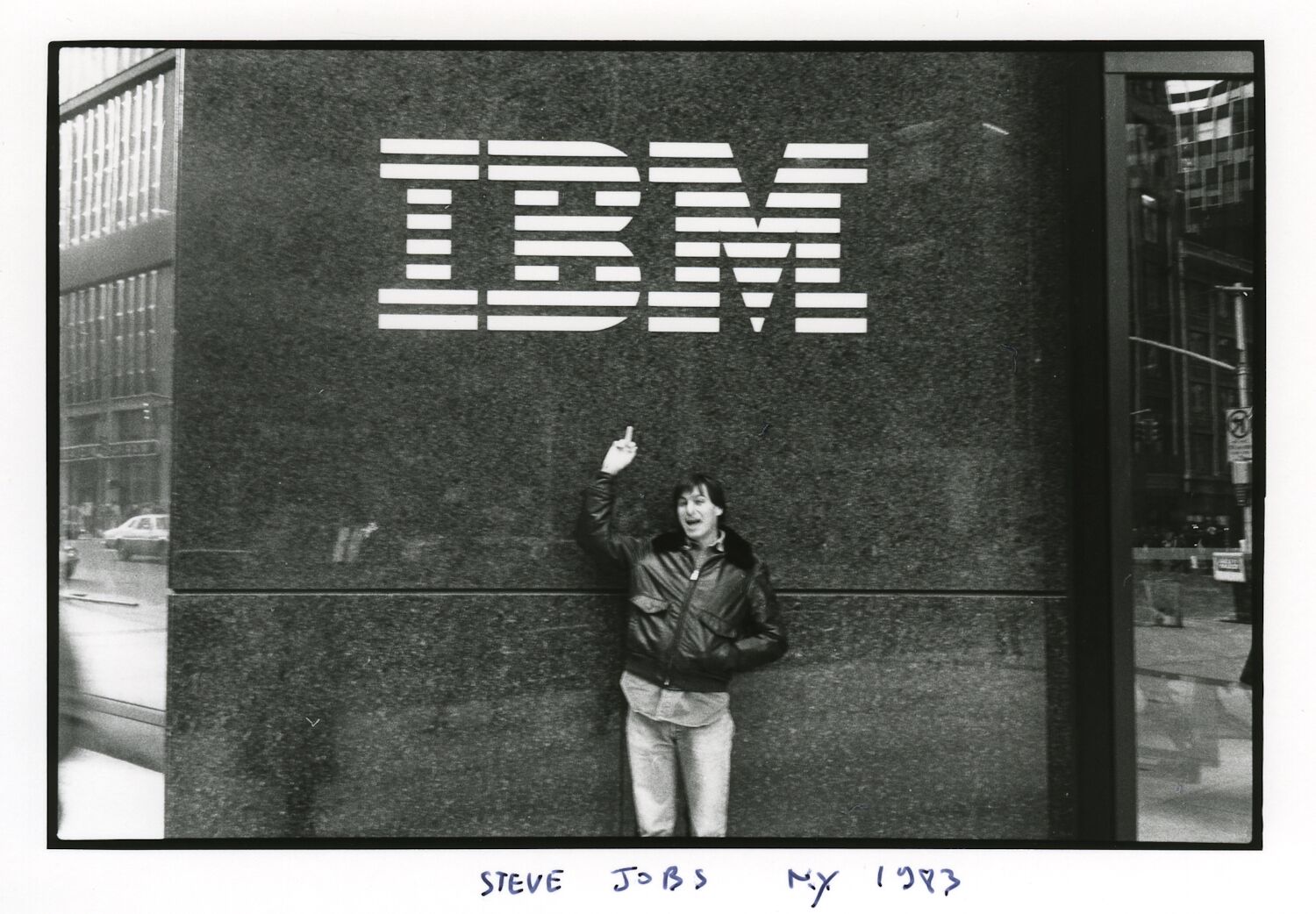

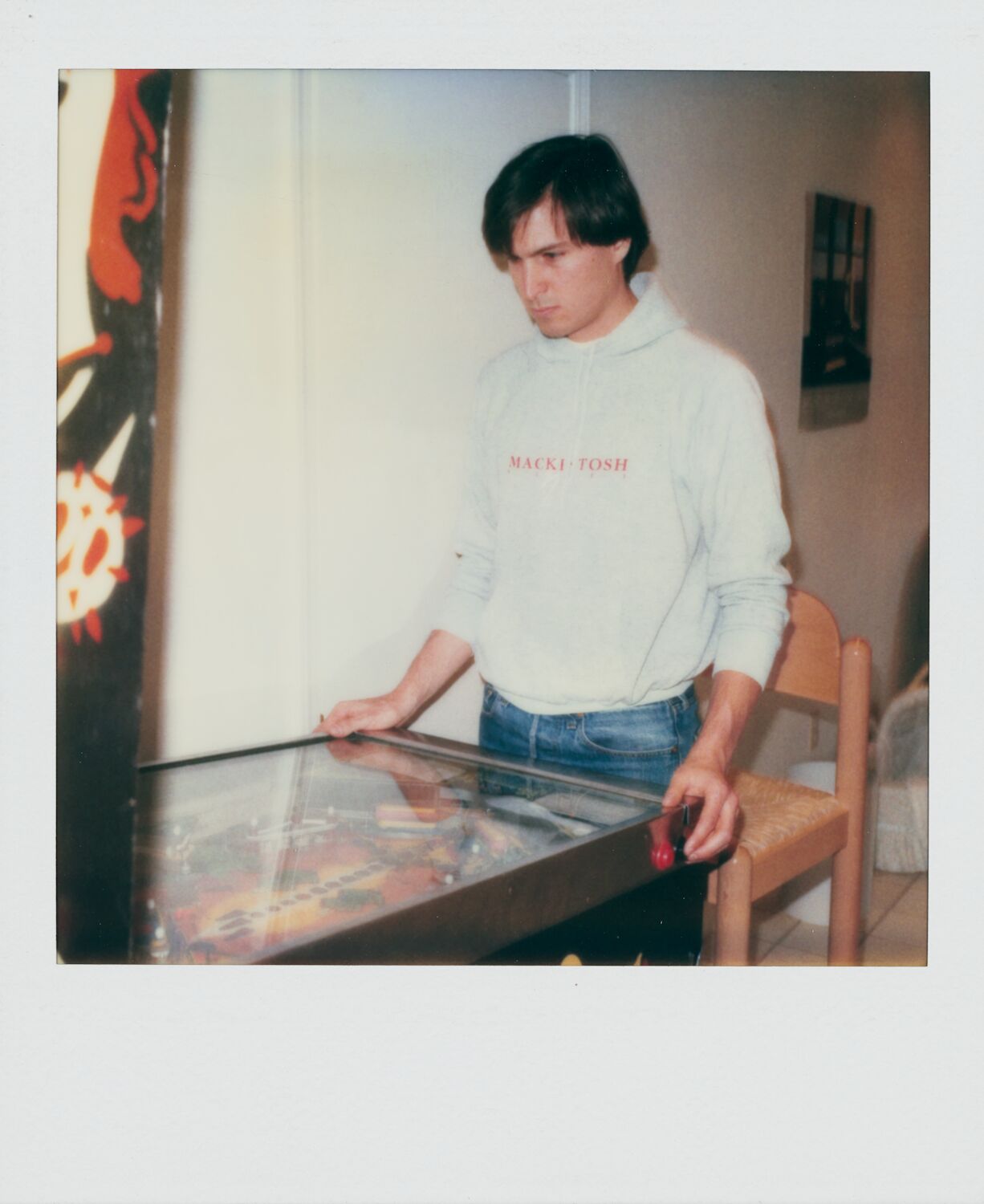

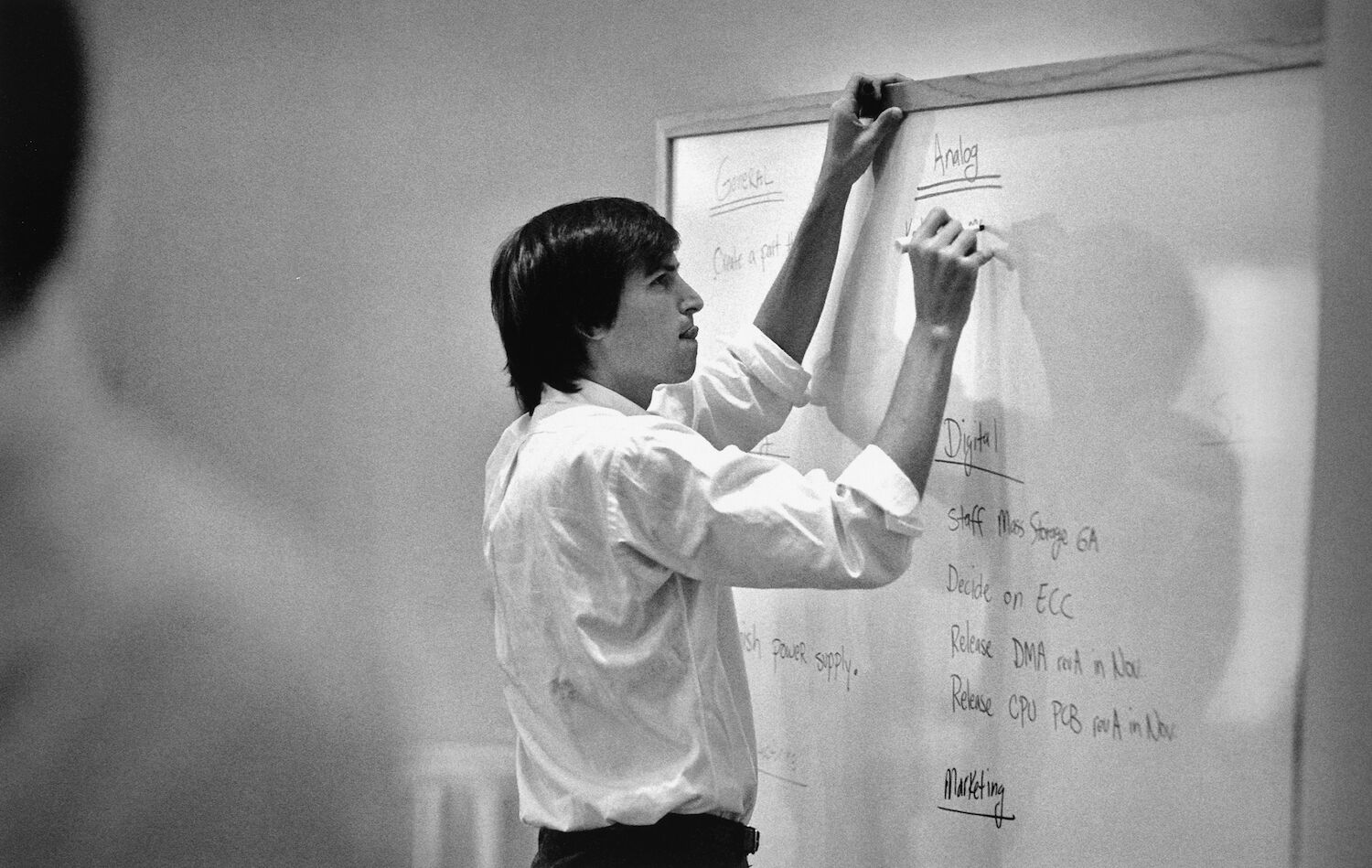

In 1976, when Steve and his friend Steve Wozniak (“Woz”) began assembling what would come to be known as the Apple I in the Jobs family’s garage, the word “computer” conjured images of hulking machines tended by professional programmers. A single company—IBM—dominated the industry. But Steve and Woz were part of a new generation of creative thinkers, engineers, and hobbyists trying to build small, cheap machines that they could program themselves.

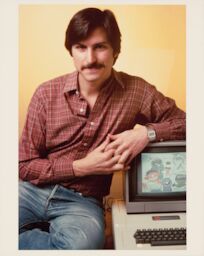

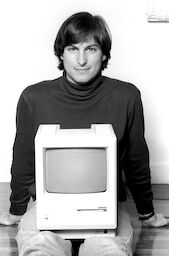

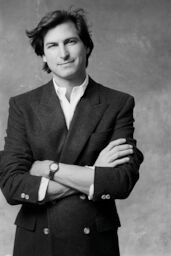

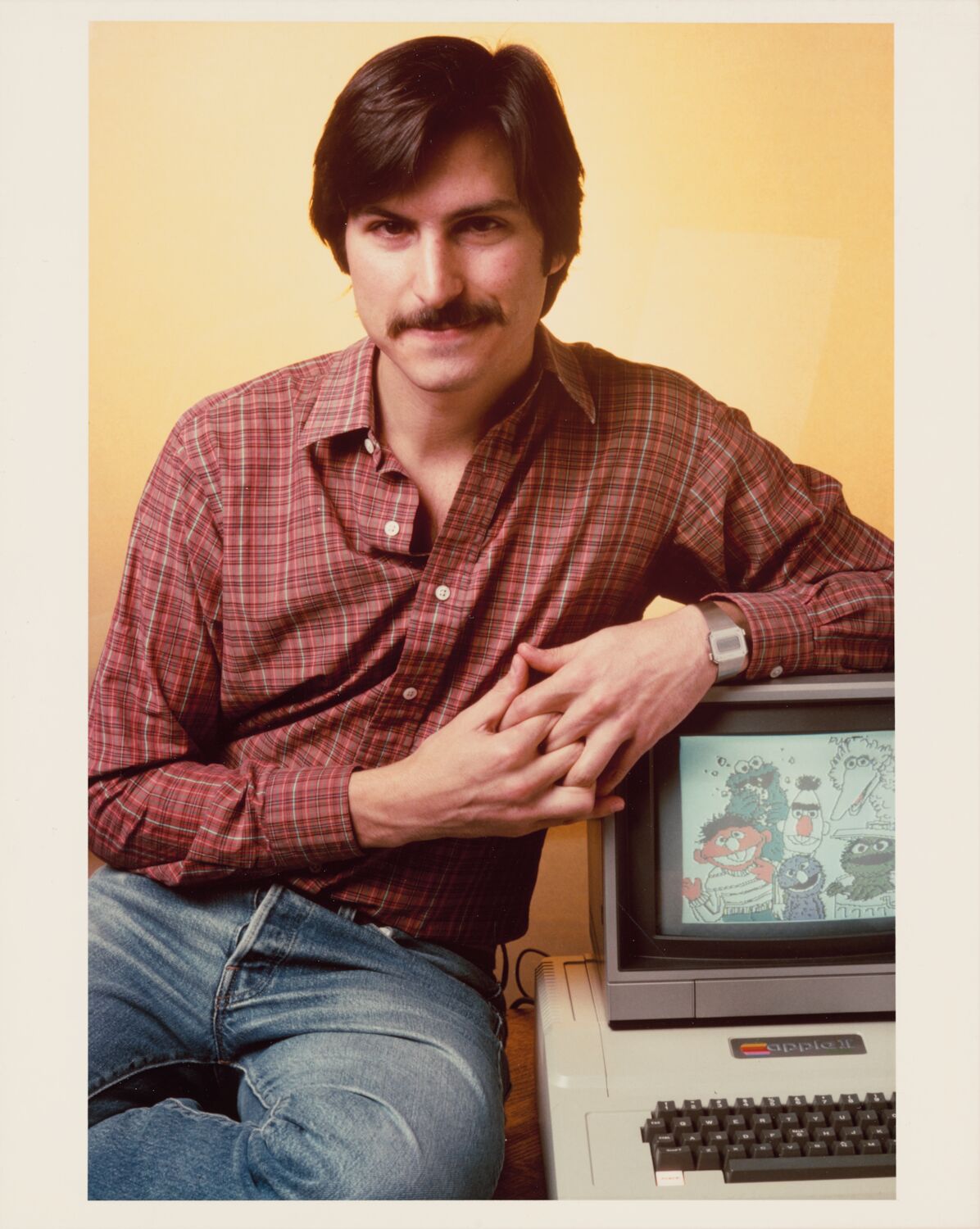

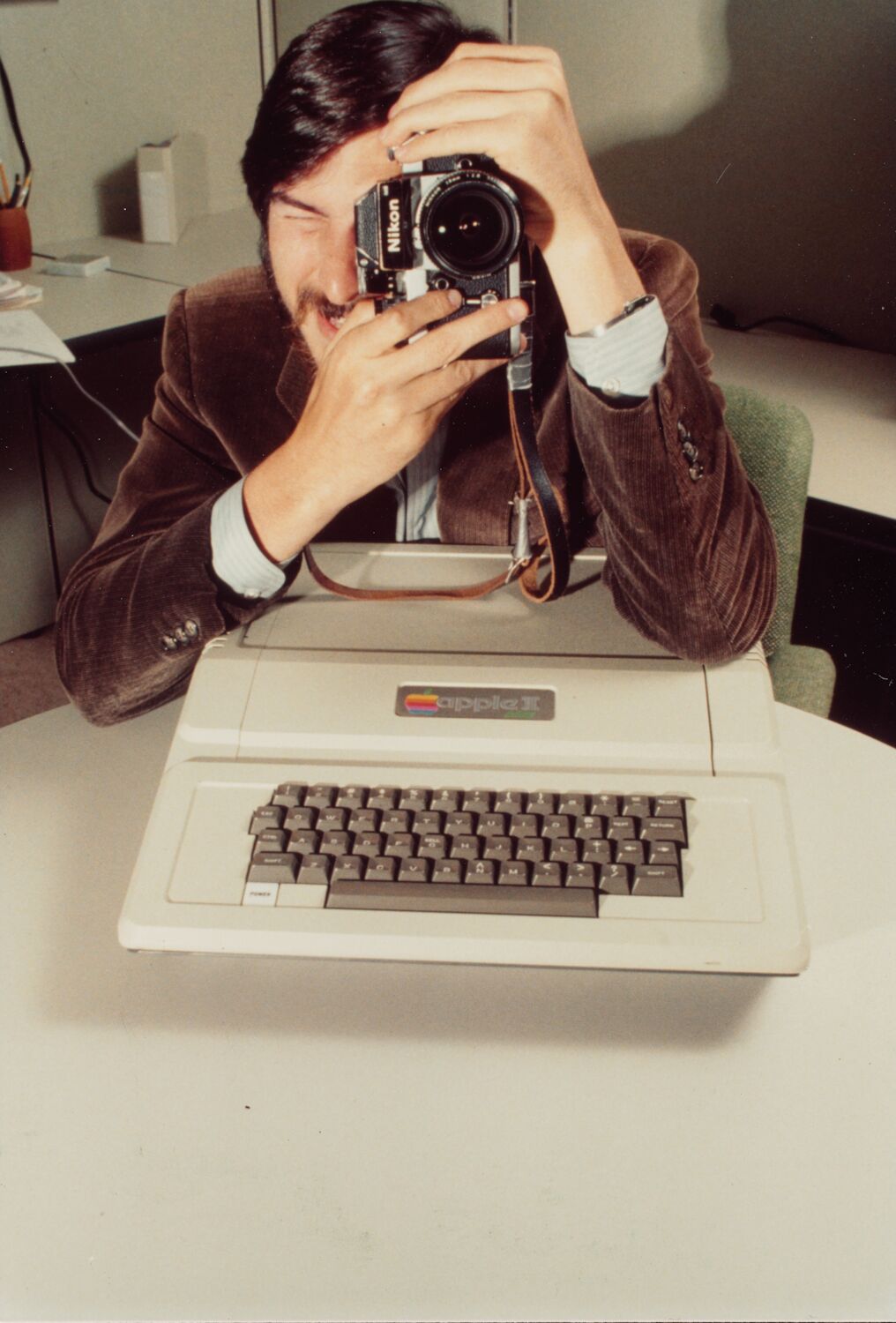

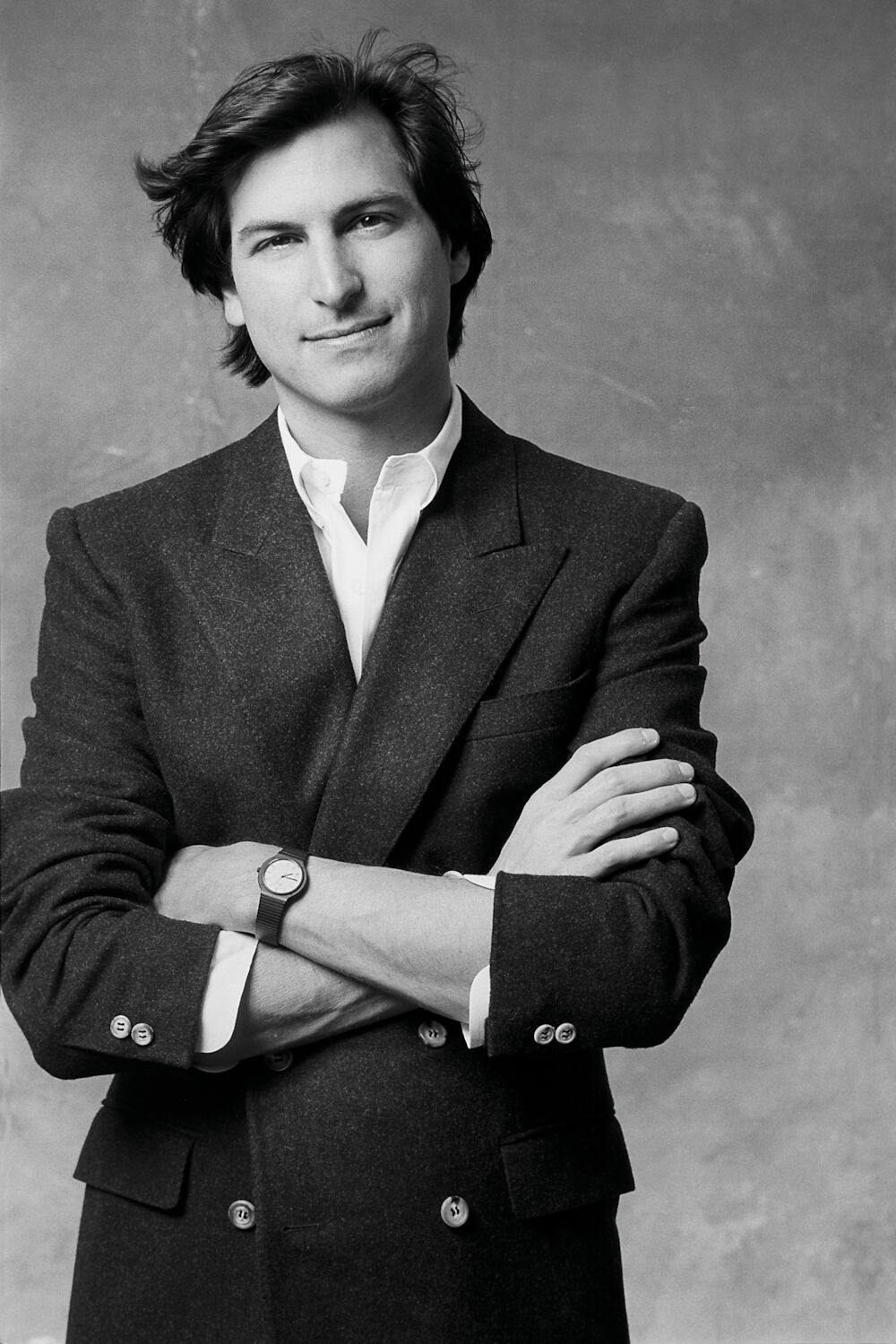

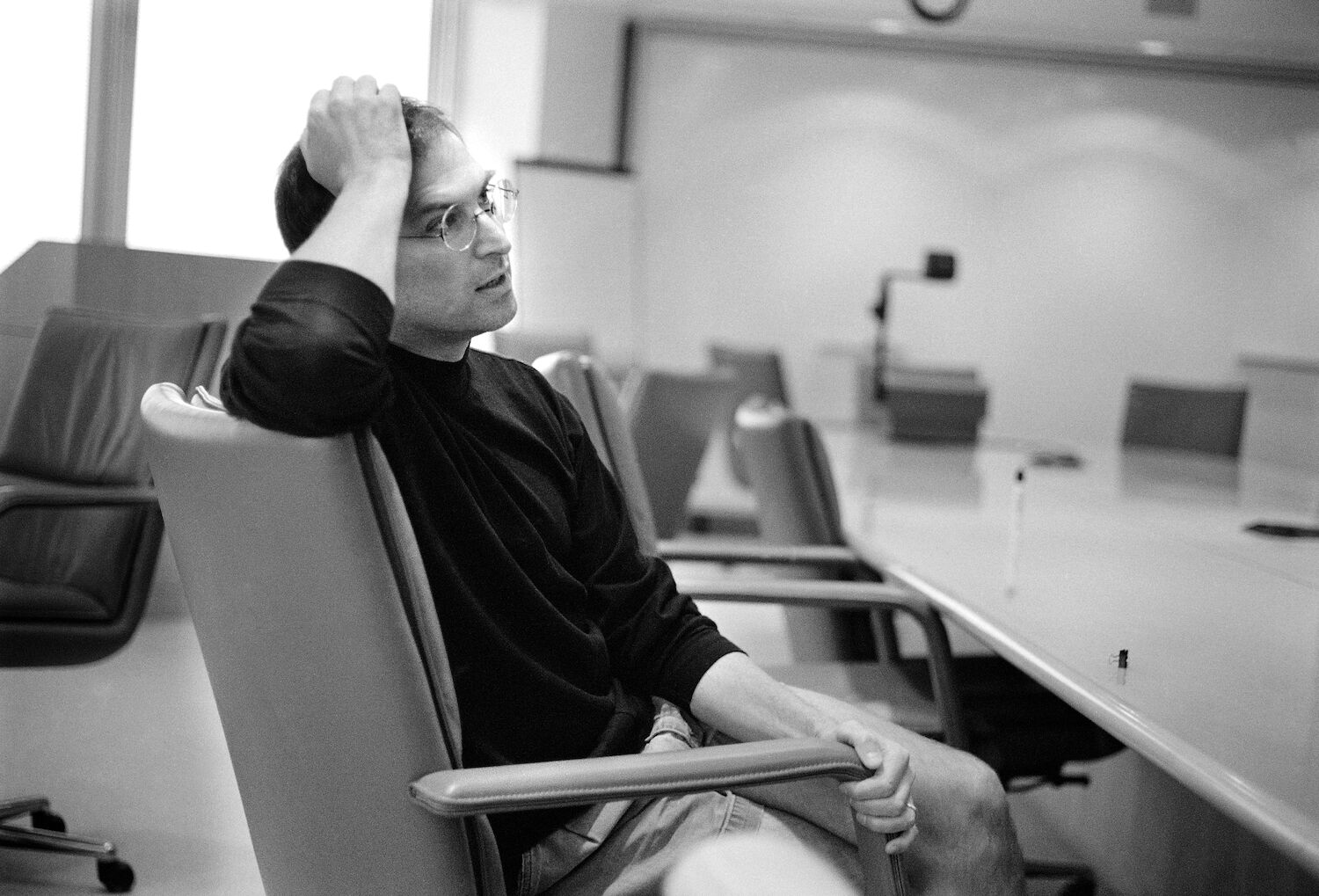

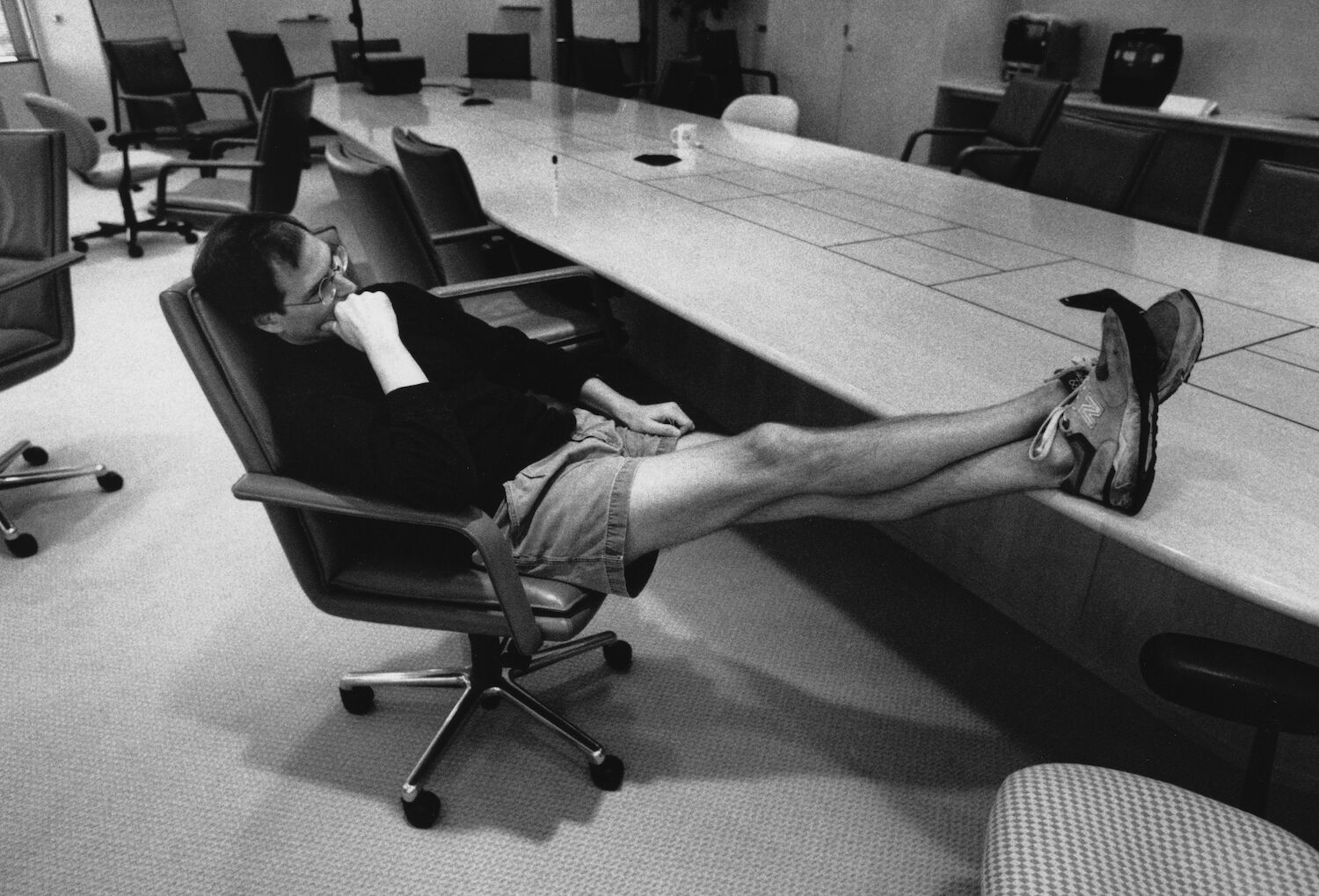

When Apple launched, Steve was twenty-one, precocious but inexperienced and unpolished. At Apple’s first board meeting, he put his bare feet on a conference room table, earning a quick rebuke from the board chair. The company’s breakthrough came with the introduction of the Apple II, a machine that could run right out of the box, with cassette storage and a built-in color screen. Within a year, Apple was one of the fastest-growing companies in America—and by the time Steve turned thirty, he was the public face of a Fortune 500 company.

Inside Apple, his ideas and passion were inspiring, but Steve’s management style was divisive. His responsibilities changed almost every year as he was assigned to and removed from various projects and teams. He began clashing with his handpicked CEO, John Sculley. In September 1985, the Apple board fired Steve.

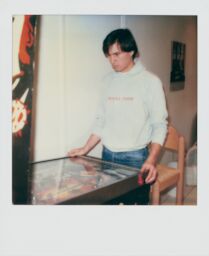

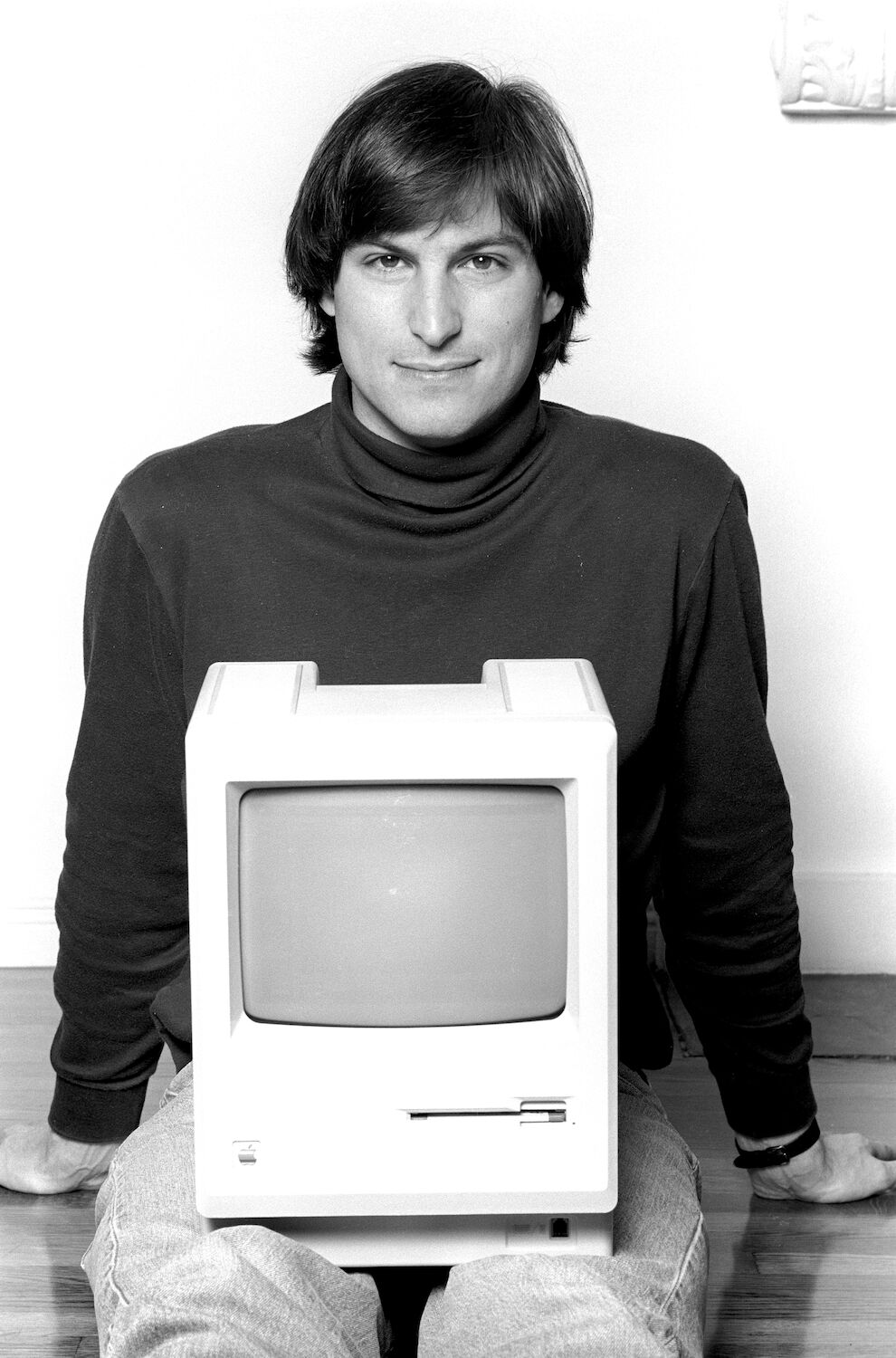

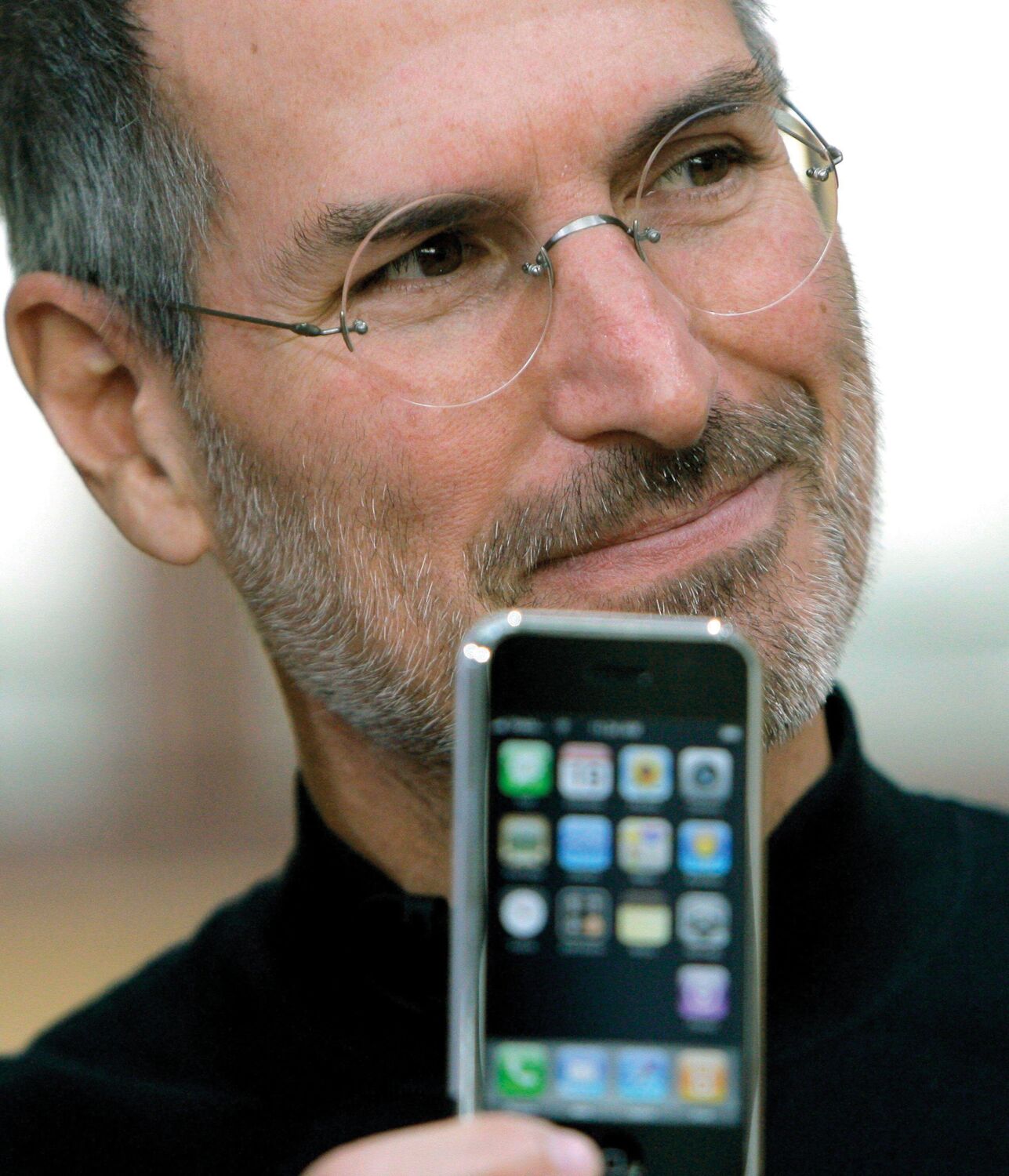

Later, when he talked about these first years at Apple, Steve focused on one thing: Macintosh, the computer that he and a tight-knit team introduced to the world in 1984. To Steve, Macintosh was everything technology should be. It was streamlined and practical, simple and sophisticated, a tool for enhancing creativity as much as productivity.

In another age, Steve believed, the people on the Macintosh team would have been writers, musicians, or artists. “The feelings and the passion that people put into it were completely indistinguishable from a poet or a painter,” he said. He called their work a form of love and their product “a computer for the rest of us,” with a mouse as well as arrow keys, desktop icons instead of programming commands, and, at startup, instead of a blinking cursor: a smile.

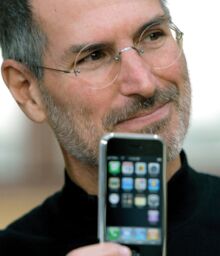

Macintosh also represented the first time Steve led a team developing a product that he believed had changed the world. “It ushered in a revolution,” Steve recalled twenty-three years later, during the rollout of another world-changing innovation: the iPhone. “I remember the week before we launched the Mac, we all got together, and we said, ‘Every computer is going to work this way. You can’t argue about that anymore. You can argue about how long it will take, but you can’t argue about it anymore.’”

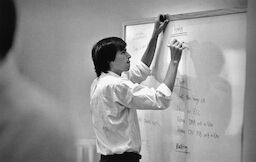

Steve on Launching Apple

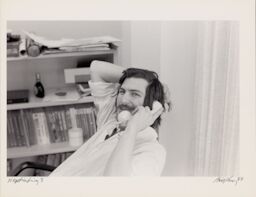

In 1984, Steve recalled the friendships behind Apple.

I met Woz when I was thirteen in a friend of mine’s garage. He was, I think, about eighteen. […] He moved down the street from a friend of mine named Bill Fernandez, and I was over at Bill’s. We were working late one night on a project, and Woz dropped by. We ended up talking for hours. I was real impressed with him. I thought he was great. He had a good sense of humor […] and we had a common interest [in electronics] that sort of bound us together even though we were totally different in every other way possible. ✂

We’re sort of like two planets in our own orbits that every so often intersect each other. There’s a bond there that will last as long as we both live.

In 1996, the year Apple celebrated its twentieth anniversary, Steve recalled how a teen hobby building computers turned into a business.

The reason we [Woz and I] built a computer was that we wanted one, and we couldn’t afford to buy one. They were thousands of dollars at that time. We were just two teenagers. We started trying to build them and scrounging parts around Silicon Valley where we could. After a few attempts, we managed to put together something that was the Apple I. All of our friends wanted them, too. They wanted to build them. It turned out that it took maybe fifty hours to build one of these things by hand. It was taking up all of our spare time because our friends were not that skilled at building them, so Woz and I were building them for them.

We thought if we could just get what’s called a printed circuit board, where you could just plug in the parts instead of having to hand-wire the whole thing, we could cut the assembly time down from maybe fifty hours to more like an hour. Woz sold his HP calculator, and I sold my VW Microbus, and we got enough money together to pay someone to design one of these printed circuit boards for us. Our goal was to just sell them as raw printed circuit boards to our friends and make enough money to recoup our calculator and transportation.

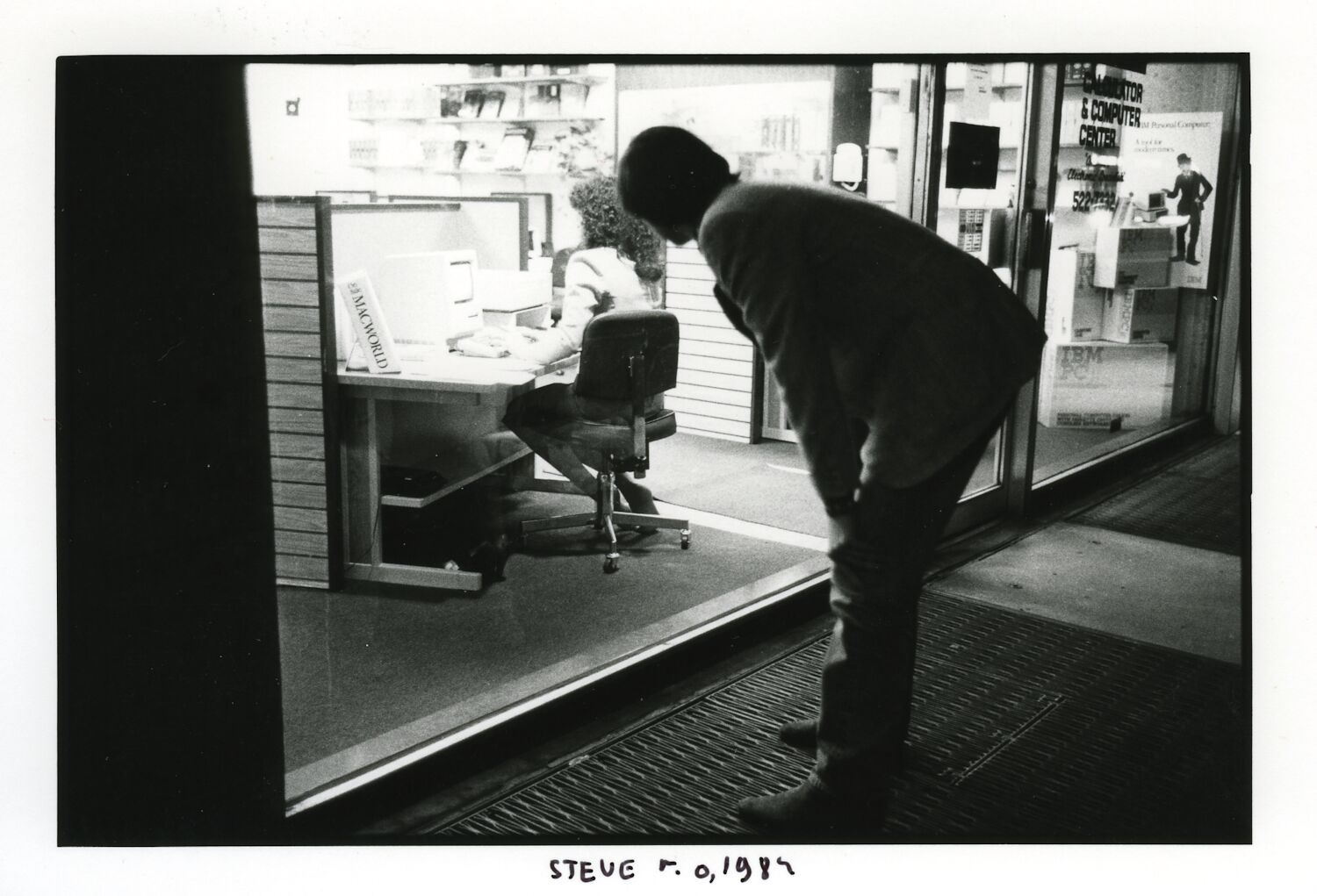

What happened was that one of the early computer [stores], in fact, the first computer store in the world, which was in Mountain View at the time, said, “Well, I’ll take fifty of these computers, but I want them fully assembled.” Which was a twist that we’d never thought of.

We went and bought the parts to build one hundred computers. We built fifty of them and delivered them. We got paid in cash and ran back and paid the people that sold us parts. Then we had the classic Marxian profit realization crisis, which was our profit wasn’t liquid—it was in fifty computers sitting on the floor.

We decided we had to start learning about sales and distribution so that we could sell the fifty computers and get back our money. That’s how we got in the business. We took our idea [for the computer] to a few companies, one where Woz worked [Hewlett-Packard] and one where I worked at the time [Atari]. Neither one was interested in pursuing it, so we started our own company.

Interview with The New Yorker

“It’s a domesticated computer.”

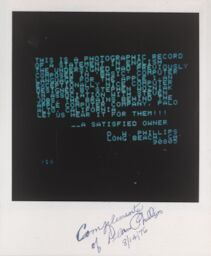

Steve’s first appearance in a national publication came in a 1977 issue of The New Yorker. The magazine sent a reporter to the First Annual Personal Computing Expo, held in the New York Coliseum. Most people at the time had never seen a personal computer.

At a booth marked “Apple Computer, Inc.,” we paused to chat with the young man in charge, who introduced himself as Steven Jobs, the company’s vice-president for operations. Mr. Jobs was pleased at the turnout for the exhibition. “I wish we’d had these personal machines when I was growing up,” he said. “People have been hearing all sorts of things about computers during the past ten years through the media. Supposedly, computers have been controlling various aspects of their lives. Yet in spite of that, most adults have no idea of what a computer really is, of what it can or can’t do.

“Now, for the first time, people can actually buy a computer for the price of a good stereo, interact with it, and find out all about it. It’s analogous to taking apart 1955 Chevys. Or consider the camera. There are thousands of people across the country taking photography courses. They’ll never be professional photographers. They just want to understand what the photographic process is all about. Same with computers.

“We started a little personal-computer manufacturing company in a garage in Los Altos in 1976. Now we’re the largest personal-computer company in the world. We make what we think of as the Rolls-Royce of personal computers. It’s a domesticated computer. People expect blinking lights, but what they find is that it looks like a portable typewriter, which, connected to a suitable readout screen, is able to display in color.

“There’s a feedback it gives to people, and the enthusiasm of the users is tremendous. We’re always asked what it can do, and it can do many things, but in my opinion the real thing it is doing right now is to teach people how to program the computer.”

Recalling Mr. Jobs’ wish that he had had such machines when he was growing up, we asked him if he would mind telling us his age.

“Twenty-two,” Mr. Jobs said.

Speech at the International Design Conference in Aspen

“Computers and society are out on a first date.”

Steve spoke to designers at this annual gathering in Aspen, Colorado, on June 15, 1983, five months after Apple introduced the Lisa computer.

How many of you are over thirty-six years old? You were born pre-computer. Computers are thirty-six years old. I think there’s going to be a little slice in the timeline of history as we look back, a pretty meaningful slice right there. A lot of you are products of the television generation. I’m pretty much a product of the television generation, but to some extent starting to be a product of the computer generation.

But the kids growing up now are definitely products of the computer generation, and in their lifetimes the computer will become the predominant medium of communication, just as the television took over from the radio, took over from even the book.

How many of you own an Apple? Any? Or just any personal computer?

Uh-oh.

How many of you have used one, or seen one, or anything like that? Good. ✂

Computers are really dumb. They’re exceptionally simple, but they’re really fast. The raw instructions that we have to feed these little microprocessors—or even these giant Cray-1 supercomputers—are the most trivial of instructions. They get some data from there, get a number from here, add two numbers together, and test to see if it’s bigger than zero. It’s the most mundane thing you could ever imagine.

But here’s the key thing: let’s say I could move a hundred times faster than anyone in here. In the blink of your eye, I could run out there, grab a bouquet of fresh spring flowers, run back in here, and snap my fingers. You would all think I was a magician. And yet I would basically be doing a series of really simple instructions: running out there, grabbing some flowers, running back, snapping my fingers. But I could just do them so fast that you would think that there was something magical going on.

And it’s the exact same way with a computer. It can do about a million instructions per second. And so we tend to think there’s something magical going on, when in reality, it’s just a series of simple instructions. ✂

One of the reasons I’m here is because I need your help. If you’ve looked at computers, they look like garbage. All the great product designers are off designing automobiles or buildings. But hardly any of them are designing computers. If we take a look, we’re going to sell 3 million computers this year, 10 million in ’86, whether they look like a piece of shit or they look great. People are just going to suck this stuff up so fast no matter what it looks like. And it doesn’t cost any more money to make them look great. They are going to be these new objects that are going to be in everyone’s working environment, everyone’s educational environment, and everyone’s home environment. We have a shot [at] putting a great object there—and if we don’t, we’re going to put one more piece-of-junk object there.

By ’86, ’87, pick a year, people are going to spend more time interacting with these machines than they do interacting with automobiles today. People are going to be spending two, three hours a day interacting with these machines—longer than they spend in the car. And so the industrial design, the software design, and how people interact with these things certainly must be given the consideration that we give automobiles today—if not a lot more.

If you take a look, what we’ve got is a situation where most automobiles are not being designed in the United States. Televisions? Audio electronics? Watches, cameras, bicycles, calculators, you name it: most of the objects of our lives are not designed in America. We’ve blown it. We’ve blown it from an industrial point of view because we’ve lost the markets to foreign competitors. We’ve also blown it from a design point of view.

And I think we have a chance with this new computing technology meeting people in the eighties—the fact that computers and society are out on a first date in the eighties. We have a chance to make these things beautiful, and we have a chance to communicate something through the design of the objects themselves. ✂

When I was going to school, I had a few great teachers and a lot of mediocre teachers. And the thing that probably kept me out of jail was the books. I could go and read what Aristotle or Plato wrote without an intermediary in the way. And a book was a phenomenal thing. It got right from the source to the destination without anything in the middle.

The problem was, you can’t ask Aristotle a question. And I think, as we look towards the next fifty to one hundred years, if we really can come up with these machines that can capture an underlying spirit, or an underlying set of principles, or an underlying way of looking at the world, then, when the next Aristotle comes around, maybe if he carries around one of these machines with him his whole life—his or her whole life—and types in all this stuff, then maybe someday, after this person’s dead and gone, we can ask this machine, “Hey, what would Aristotle have said? What about this?” And maybe we won’t get the right answer, but maybe we will. And that’s really exciting to me. And that’s one of the reasons I’m doing what I’m doing.

So, what do you want to talk about?

Steve answered questions at two conference sessions.

How are these computers all going to work together? They’re probably going to work together a lot like people do. Sometimes they’re going to work together really well, and other times they’re not going to work together so well. ✂

What’s happened, there’s been a few installations where people have hooked these things together. The one installation that stands out is at Xerox Palo Alto Research Center, or PARC, for short. And they hooked about a hundred computers together on what’s called a local area network, which is just a cable that carries all this information back and forth. […]

Then an interesting thing happened. There were twenty people interested in volleyball. So a volleyball distribution list evolved, and then, when the volleyball game next week was changed, you’d write a quick memo and send it to the volleyball distribution list. Then there was a Chinese food cooking list. And before long, there were more lists than people.

And it was a very, very interesting phenomenon, because I think that that’s exactly what’s going to happen as we start to tie these things [computers] together: they’re going to facilitate communication and facilitate bringing people together in the special interests that they have.

And we’re about five years away from really solving the problems of hooking these computers together in the office. And we’re about ten to fifteen years away from solving the problems of hooking them together in the home. A lot of people are working on it, but it’s a pretty fierce problem.

Now, Apple’s strategy is really simple. What we want to do is put an incredibly great computer in a book that you carry around with you, that you can learn how to use in twenty minutes. That’s what we want to do. And we want to do it this decade. And we really want to do it with a radio link in it so you don’t have to hook up to anything—you’re in communication with all these larger databases and other computers. We don’t know how to do that now. It’s impossible technically. ✂

We’re trying to get away from programming. We’ve got to get away from programming because people don’t want to program computers. People want to use computers. ✂

We [at Apple] feel that, for some crazy reason, we’re in the right place at the right time to put something back. And what I mean by that is, most of us didn’t make the clothes we’re wearing, and we didn’t cook or grow the food that we eat, and we’re speaking a language that was developed by other people, and we use a mathematics that was developed by other people. We are constantly taking.

And the ability to put something back into the pool of human experience is extremely neat. I think that everyone knows that in the next ten years we have the chance to really do that. And we [will] look back—and while we’re doing it, it’s pretty fun, too—we will look back and say, “God, we were a part of that!” ✂

We started with nothing. So whenever you start with nothing, you can always shoot for the moon. You have nothing to lose. And the thing that happens is—when you sort of get something, it’s very easy to go into cover-your-ass mode, and then you become conservative and vote for Ronnie. So what we’re trying to do is to realize the very amazing time that we’re in and not go into that mode. ✂

I can’t tell you why you need a home computer right now. I mean, people ask me, “Why should I buy a computer in my home?”

And I say, “Well, to learn about it, to run some fun simulations. If you’ve got some kids, they should probably know about it in terms of literacy. They can probably get some good educational software, especially if they’re younger.

“You can hook up to The Source and, you know, do whatever you’re going to do. Meet women, I don’t know. But other than that, there’s no good reason to buy one for your house right now. But there will be. There will be.” ✂

I don’t think finance is what drives people at Apple. I don’t think it’s money, but feeling like you own a piece of the company, and this is your damn company, and if you see something … We always tell people, “You work for Apple first and your boss second.” We feel pretty strongly about that. ✂

When you have a million people using something, then that’s when creativity really starts to happen on a very rapid scale. […] We need some revolutions like [the] Lisa [computer], but we also then need to get millions of units out there and let the world innovate—because the world’s pretty good at innovating, we’ve found.

On the Macintosh

Macintosh was less than a year old—but clearly poised to transform the personal computer industry—when Steve reflected on its significance with reporter David Sheff.

One of the things I love is that with Macintosh, you can write memos that are Times Roman or Helvetica, or you can throw in an Old English if you want to have a little fun for a party, you know, for a volleyball announcement. Or you can use a very serious font for something very serious. And you can express yourself.

It’s sort of like in 1844, the telegraph was invented, and it was an amazing breakthrough in communications. And you actually could send messages from New York to San Francisco in an afternoon. And some people talked about putting a telegraph on every desk in America to improve productivity.

But it wouldn’t have worked. It wouldn’t have worked. And the reason it wouldn’t have worked was because you would have had to learn this whole sequence of strange incantations—Morse code in this case, dots and dashes in this case—to use the telegraph. And it took about forty hours to learn how to use Morse code. And a majority of people would never have learned how to use Morse code.

So fortunately, in the 1870s, Alexander Graham Bell filed the patents for the telephone—another radical breakthrough in communications that performed basically the same function, but people already knew how to use it. The neatest thing about it was that, in addition to allowing you to communicate with just words, it allowed you to sing. It allowed you to intone your words with meaning beyond the simple linguistics.

We’re in the same exact parallel situation today. Some people are saying we need to put an IBM PC on every desk in America to improve productivity. But it won’t work. The special incantations you have to learn this time are slash-qz’s and things like that. Most people are not going to learn slash-qz’s any more than they’re going to learn Morse code.

And that’s what Macintosh is all about. It’s the first “telephone” of our industry. But the neatest thing about it to me is, the same as the telephone to the telegraph, Macintosh lets you sing. It lets you use special fonts. It lets you make drawings and pictures or incorporate other people’s drawings or pictures into your documents.

Even in business, you’re seeing five-page memos get compressed down to a one-page memo because there’s a picture to express the key concept. And so we’re seeing less paper flying around and more quality of communication.

And it’s more fun. There’s always been this myth that really neat, fun people at home all of [a] sudden get very dull and boring and serious when they come to work, and it’s simply not true. So if we can again inject that liberal-arts spirit into this very serious realm of business, I think it would be a worthwhile contribution.

Speech to Apple Employees

“Was George Orwell right about 1984?”

Steve introduced the Macintosh and its iconic commercial, which ran during the 1984 Super Bowl, at an Apple sales meeting in October 1983.

Hi, I’m Steve Jobs.

It is 1958. IBM passes up the chance to buy a young, fledgling company that has invented a new technology called xerography. Two years later, Xerox is born. And IBM has been kicking themselves ever since.

It is ten years later, the late sixties. Digital Equipment [DEC] and others invent the minicomputer. IBM dismisses the minicomputer as too small to do serious computing, and therefore unimportant to their business. DEC grows to become a multi-hundred-million-dollar corporation before IBM finally enters the minicomputer market.

It is now ten years later, the late seventies. In 1977, Apple, a young, fledgling company on the West Coast, invents the Apple II, the first personal computer as we know it today. IBM dismisses the personal computer as too small to do serious computing and unimportant to their business.

The early eighties, ’81. Apple II has become the world’s most popular computer. Apple has grown to a $300 million company, becoming the fastest-growing corporation in American business history, with over fifty competitors vying for a share. IBM enters the personal-computer market in November ’81 with the IBM PC.

1983. Apple and IBM emerge as the industry’s strongest competitors, each selling approximately one billion dollars’ worth of personal computers in 1983. Each will invest greater than $50 million for R&D and another $50 million for television advertising in 1984, totaling almost one quarter of a billion dollars combined.

The shakeout is in full swing. The first major firm goes bankrupt, with others teetering on the brink. Total industry losses for ’83 outshadow even the combined profits of Apple and IBM for personal computers.

It is now 1984. It appears IBM wants it all. Apple is perceived to be the only hope to offer IBM a run for its money. Dealers initially welcoming IBM with open arms now fear an IBM-dominated and controlled future. They are increasingly and desperately turning back to Apple as the only force that can ensure their future freedom.

IBM wants it all, and is aiming its guns on its last obstacle to industry control: Apple. Will Big Blue dominate the entire computer industry? [Audience: No!] The entire information age? [Audience: No!] Was George Orwell right about 1984?

[Steve runs the “1984” commercial. Directed by Ridley Scott, the ad depicts a dystopian, Orwellian world. In one scene, people dressed in gray, their heads shaved, sit expressionless in front of a large screen on which a dictator drones nonsense. A woman in bright red running shorts and a Macintosh shirt bursts into the room. She hurls a hammer at the screen, destroying it. The commercial ends with a promise: “On January 24th, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like ‘1984.’”]

[There is tumultuous applause and shouting from the audience; once it dies down, Steve resumes.] That ad is going to run one week before Macintosh is introduced. And our ad agency that put it together is here today, Chiat/Day. Jay Chiat is here, the principal. Lee Clow and Steve Hayden, [who] wrote the copy and did the creative, are also here.

You might—I guess they just heard what you thought.

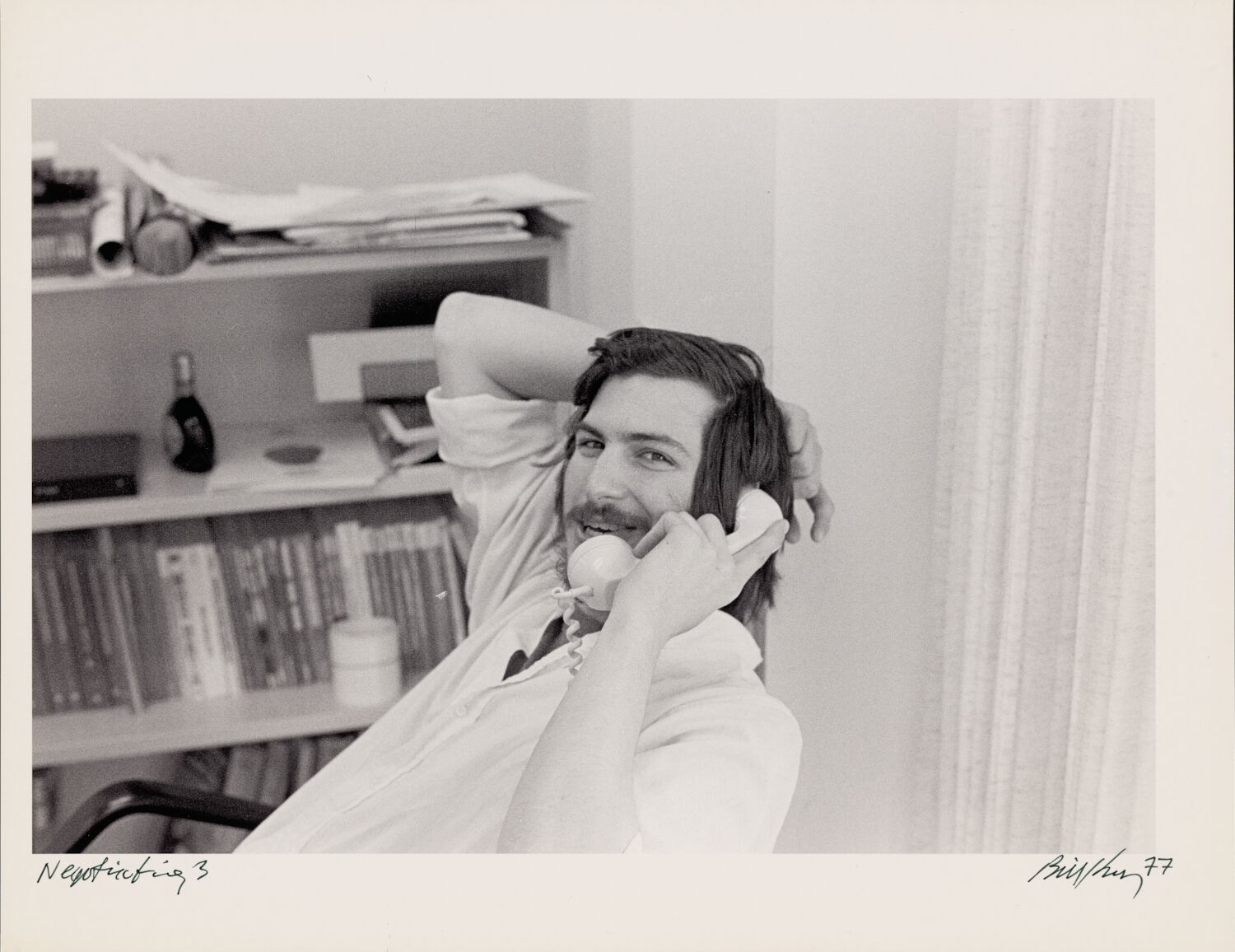

Interview with Michael Moritz

“Your aesthetics get better as you make mistakes.”

Steve and Michael Moritz, a reporter who would soon switch careers and become a venture capitalist, spoke at Steve’s office at Apple in May 1984. They covered a wide range of topics, including Steve’s thoughts on product design.

Steve Jobs: I went around and looked at Cuisinarts when we were designing Mac. It was like my Cuisinart week.

Michael Moritz: But no other particular products [influenced you]? Say, from the late seventies or something.

SJ: Well, we’re around automobiles our whole lives. I’ve never been a car guy, but I’ve always loved Volkswagen Beetles. I’ve always loved Volkswagen vans, actually, too.

Just a bunch of little things: wine labels, paintings in galleries. Just simple things. Not anything real profound, just lots and lots of little things. I don’t think my taste in aesthetics is that much different than a lot of other people’s. The difference is that I just get to be really stubborn about making things as good as we all know they can be. That’s the only difference.

MM: Yeah, I think you’re being modest.

SJ: Well, things get more refined as you make mistakes. I’ve had a chance to make a lot of mistakes. Your aesthetics get better as you make mistakes. But the real big thing is: if you’re going to make something, it doesn’t take any more energy—and rarely does it take more money—to make it really great. All it takes is a little more time. Not that much more. And a willingness to do so, a willingness to persevere until it’s really great.

But aesthetics? I think aesthetics are a lot like singing. Joanie [Baez] has a beautiful voice, but the reason her voice is beautiful isn’t because her voice is just beautiful. It’s because she has an incredibly good ear. She can listen to somebody speak for thirty seconds and imitate their voice almost perfectly. Her ear is superb. And I think, in the same way, good aesthetics result from just your eye. An instinct of what you see, not so much what you do. ✂

SJ: I want to build products that are inherently smaller than any of the products on the market today. And when you make things smaller, you have the ability to make them more precisely. Obviously, a perfect example of that is a watch. It’s beautiful, but the precision has to be the scale of the object itself, and so you make it very precise. And as our products get smaller, we have the opportunity to do that. So, obviously, I would like everything to be smaller.

I also think that it’s really nice to be able to carry products around. Even if they’re not portable, it’s very nice to be able to have a handle on them that says, “Pick me up and move me when you want to change where I am.” Carry them from room to room, or from office to office. Lisa’s too heavy to carry from office to office, or room to room, or home on the weekends. So the question is, “How do we find a way to package that same functionality into something that we can carry around with us and that is smaller, obviously—and be able to express the form of that more precisely?” That’s where we’re going in the future, those directions. ✂

MM: What are the uglier, offensive designs of products, or are there just too many to list?

SJ: Yeah—pick any car before three years ago, you know? Pick most cars today. Anything. Just look around the room. Tables, chairs: all ugly. You can ask me, what am I doing in this office? But anyway, most things are not very nice.

The telephone’s a perfect example. The only telephone that’s ever been any good is the original one and the Trimline. The Trimline is the only decent one. What they’ve done to the new stuff is just garbage. ✂

SJ: [At Apple] we’re just getting simpler and simpler and simpler. Very, very simple. Simple. ✂

SJ: Have you ever seen HP’s buildings over on Page Mill Road, the original ones? They’re really neat. They’ve got these scalloped roofs, and they face the glass north, and you can actually put solar collectors on them, if you wanted to. They stick out. In a building, they make a whole glass wall. And so people work down there, and they get tons of natural light coming in. Just tons.

The problem with these buildings [at Apple] is there’s no light. I mean, you spend five minutes outside, and you walk in here, it’s really dark, and you can’t see anything. And we’re all sort of like living in these little tiny caverns.

I just want a ton of natural light. ✂

MM: Was all the stuff about Big Brother [in the “1984” commercial] very conscious of the IBM stuff, or was that something that outsiders quickly interpreted, and you guys weren’t exactly going to—

SJ: Deny it?

MM: Deny it.

SJ: Well, the best response to that was the response given, I think, in Fortune, which was, “If seeing Big Brother in 1984 connotes IBM to a large number of people, that says more about IBM’s image problem than our intentions.”

In truth: of course, we saw the analogy. And I think that we were saying two things. I think the first thing we were saying was, this image of computers as sort of a centralized group of people having control of very powerful machines to keep track of us, that iconic fear in our minds—we were commenting on that cultural fear that we have.

And of course, one couldn’t—you’d have to be an idiot not to see the parallels to IBM.

Interview with Newsweek

“I want to build things.”

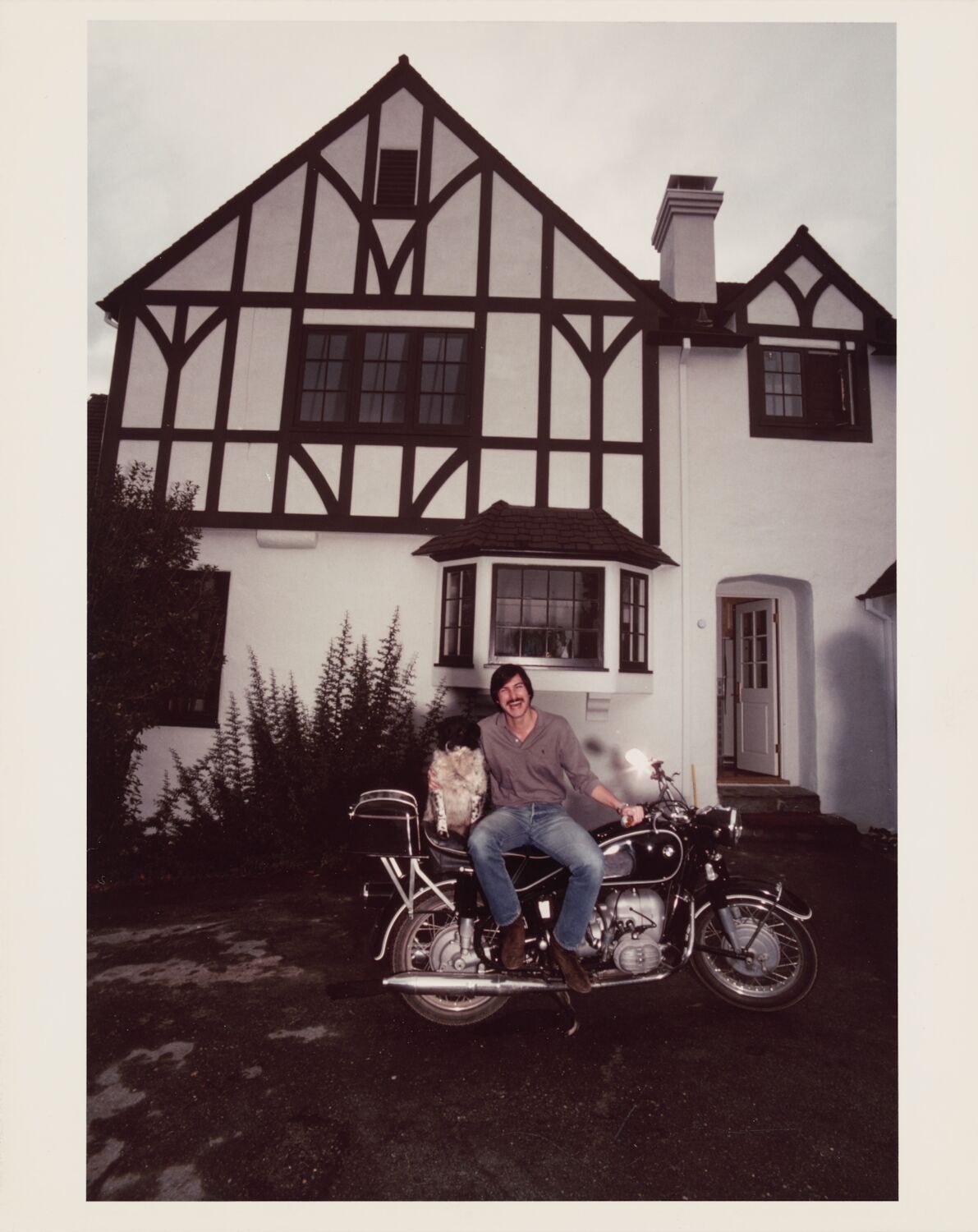

Steve left Apple in September 1985, after losing a power struggle with CEO John Sculley. The departure was officially a resignation, but Steve considered it a betrayal. A few weeks later, he spoke to Newsweek.

Newsweek: How did you react when you heard the [Apple] board’s decision [to sue you]? These were people that you knew and worked with for a long time.

Steve Jobs: Oh, yeah. I mean, in my wildest imagination, I couldn’t have come up with such a wild ending to all of this. I had hoped that my life would take on the quality of an interesting tapestry where I would have weaved in and out of Apple: I would have been there a period of time, and maybe I would have gone off and done something else to contribute, but connected with Apple, and then maybe come back and stay for a lengthy time period, and then go off and do something else. But it’s just not going to work out that way. So I had ten of the best years of my life, you know. And I don’t regret much of anything. ✂

I personally, man, I want to build things. I’m thirty. I’m not ready to be an industry pundit. I got three offers to be a professor during this summer, and I told all of the universities that I thought I would be an awful professor. What I’m best at doing is finding a group of talented people and making things with them. I respect the direction that Apple is going in. But for me personally, you know, I want to make things. And if there’s no place for me to make things there, then I’ll do what I did twice before. I’ll make my own place. You know, I did it in the garage when Apple started, and I did it in the metaphorical garage when Mac started. ✂

SJ: Though the outside world looks at success from a numerical point of view, my yardstick might be quite different than that. My yardstick may be how every computer that’s designed from here on out will have to be at least as good as a Macintosh. ✂

SJ: I used to go into work, I’d get there, and I would have one or two phone calls to perform, a little bit of mail to look at. But—this was in June, July—most of the corporate management reports stopped flowing by my desk. A few people might see my car in the parking lot and come over and commiserate.

And I would get depressed and go home in three or four hours, really depressed. I did that a few times, and I decided that was mentally unhealthy. So I just stopped going in. You know, there was nobody really there to miss me.

Q: Do you feel that they have taken your company away from you?

SJ: To me, Apple exists in the spirit of the people that work there, and the sort of philosophies and purpose by which they go about their business. So if Apple just becomes a place where computers are a commodity item and where the romance is gone, and where people forget that computers are the most incredible invention that man has ever invented, then I’ll feel I have lost Apple. But if I’m a million miles away and all those people still feel those things and they’re still working to make the next great personal computer, then I will feel that my genes are still in there. ✂

SJ: One of the five most difficult days was that day John [Sculley, Apple’s CEO] said at the analysts meeting about there not being a role for me in the future, and he said it again in another analysts meeting a week later. He didn’t say it to me directly; he said it to the press. You’ve probably had somebody punch you in the stomach and it knocks the wind out of you and you can’t breathe. If you relax, you’ll start breathing again. That’s how I felt all summer long. The thing I had to do was try to relax. It was hard. But I went for a lot of long walks in the woods and didn’t really talk to a lot of people. ✂

Q: You’ve talked about being tough to get along with, having a rough-edge personality. Did you contribute in some way to your own downfall?

SJ: You know, I’m not a sixty-two-year-old statesman that’s traveled around the world all his life. So I’m sure that there was a situation when I was twenty-five that if I could go back, knowing what I know now, I could have handled much better. And I’m sure I’ll be able to say the same thing when I’m thirty-five about the situation in 1985. I can be very intense in my convictions. And I don’t know—all in all, I kind of like myself, and I’m not that anxious to change.

Q: But has this experience changed you?

SJ: Oh, this has—yeah, I think I am growing from this, and I think I’m learning a lot from it. I’m not sure how or what yet. But yes, I feel that way. I’m not bitter; I’m not bitter. ✂

Q: There’s been a lot in the press about your interest in Buddhism, vegetarianism.

SJ: As we descend into the isms.

Q: The isms. Are you still interested in those things?

SJ: Well, I don’t know what to say. I mean, I don’t eat meat, and I don’t go to church every Sunday.

Q: They said at some point you had thought of going to Japan and sitting in a monastery.

SJ: Yeah, yeah. I’m glad I didn’t do that. I know this is going to sound really, really corny. But I feel like I’m an American, and I was born here. And the fate of the world is in America’s hands right now. I really feel that. And you know, I’m going to live my life here and do what I can to help.

Part II, 1985–1996

“You never achieve what you want without falling on your face a few times.”

The years after Steve left Apple were among the toughest of his career—and the most formative.

Determined to build a new great computer company, he started NeXT with several members of the Macintosh team. “We’ll make a whole bunch of mistakes, but at least they’ll be new and creative ones,” he predicted.

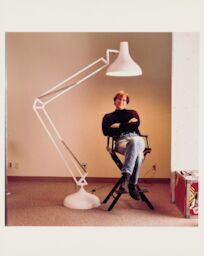

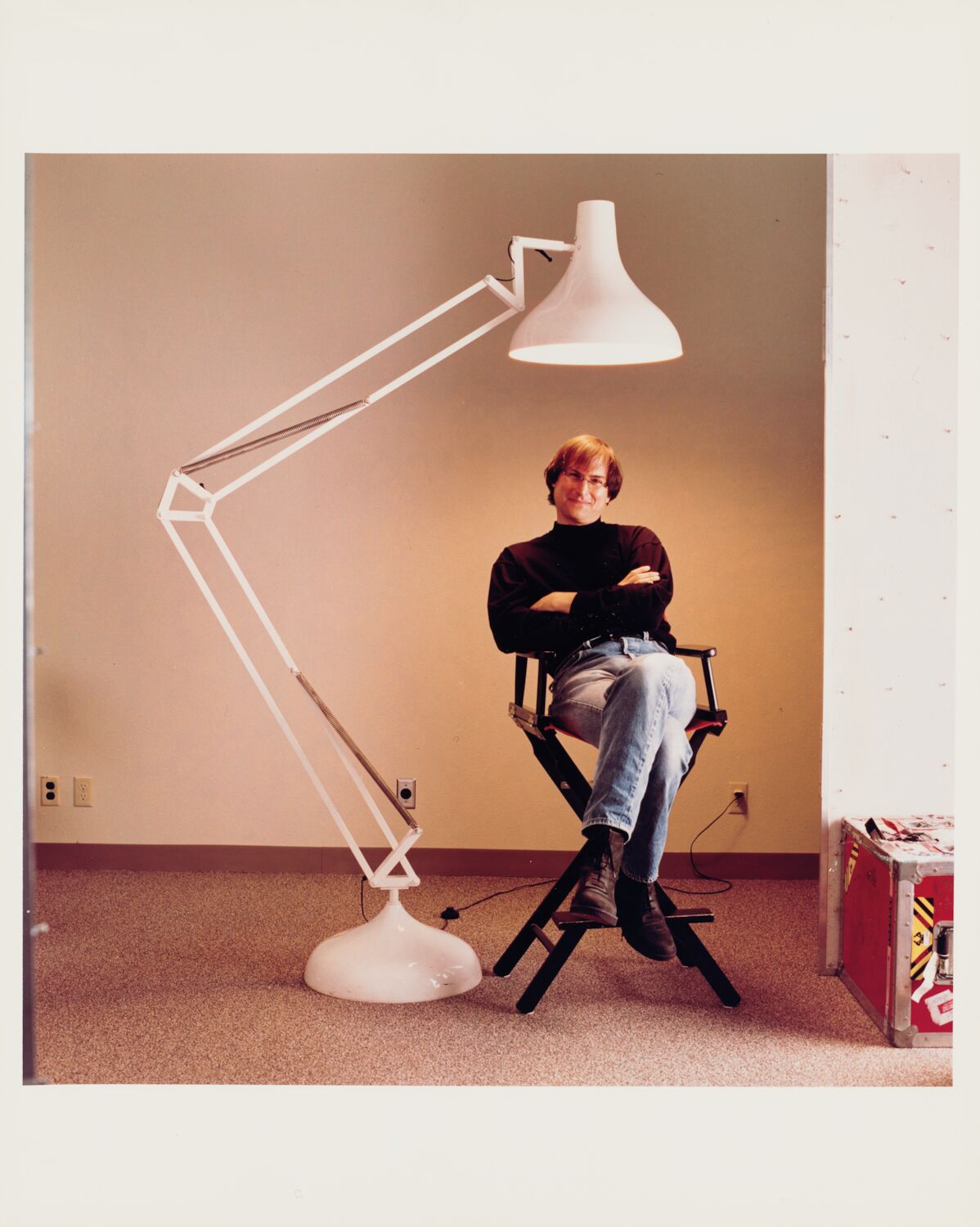

Around the same time, Steve invested $10 million in a small company called Pixar. It was a tiny computer graphics operation, newly spun off from filmmaker George Lucas’s empire. The technical expertise at Pixar attracted Steve; its initial product was a high-end graphics computer that cost more than $100,000.

Both NeXT and Pixar quickly ran into trouble. The NeXT computer system, which debuted in 1988, was powerful and packed with the humanistic touches Steve loved. It was visually striking and intuitive to use, with high-quality audio and the complete works of Shakespeare built in. But it was also late to market and expensive—and it sold poorly. Within six years of NeXT’s launch, the entire founding team, other than Steve, had resigned.

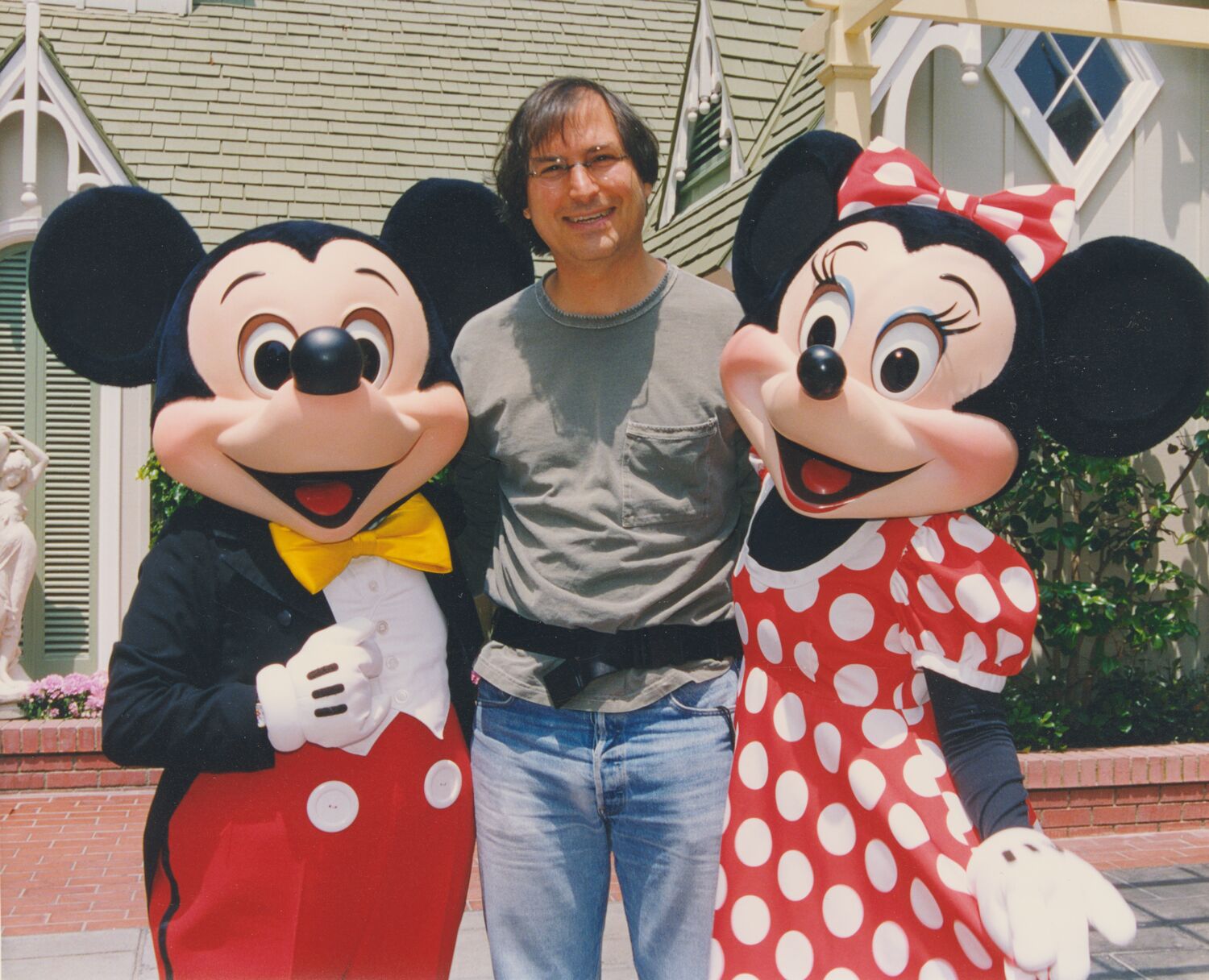

Pixar, meanwhile, was eking out an existence selling computers and software and, later, animating commercials. The company was also making award-winning short films that charmed Steve. This use of technology in service of brilliant storytelling embodied one of his favorite things: work at the intersection of technology and the liberal arts. The short films fired Steve’s enthusiasm and kept him writing check after check to Pixar, ultimately investing some $60 million.

But the films were, as Steve put it, “in the background,” not the company’s focus. He described Pixar’s early business strategy as “find a way to pay the bills,” and he later speculated that the only reason the company didn’t fall apart then was that the leadership team “would all get depressed … but not all of us at once.”

If at times in these years he seemed disappointed by the possibilities of technology—“this stuff doesn’t change the world. It really doesn’t,” he told a reporter in an uncharacteristic flash of pessimism—his world was also expanding beyond his work. He treasured his privacy, saying of his public persona, “I think of it as my well-known twin brother. It’s not me.”

Steve learned how to hone a company to its essence, even when it was painful. He shifted NeXT’s focus to selling software. The shift meant closing a factory and laying off more than two hundred of NeXT’s five hundred and thirty employees. Meanwhile, Pixar stripped away its advertising and hardware businesses and entered into an agreement with Disney, all to pursue what sometimes seemed an impossible dream: to make fully computer-animated feature films.

After nearly a decade of difficulty, the streamlined NeXT and Pixar both transformed into unlikely success stories. At the end of 1995, Pixar premiered Toy Story in the same month it held its initial public offering. A year later, Apple, in need of operating-system software, bought NeXT for $427 million. “If you really look closely,” Steve liked to say, “most overnight successes took a long time.”

Steve on Starting NeXT

A few weeks after starting NeXT, Steve spoke with Newsweek about the original insight for the company.

I had been reading some biochemistry, recombinant DNA literature. [I had recently met] Paul Berg, the inventor of some of the recombinant techniques. I called him up, and I said, “You remember me. I’m ignorant about this stuff, but I’ve got a bunch of questions about how it works, and I’d love to have lunch with you.” So we had lunch at Stanford. He was showing me how they were doing gene repairing. Actually, it’s straightforward, it’s kind of neat. It smells a lot like some of the concepts you find in computer science. So he was explaining how he does experiments in a wet laboratory and they take a week or two or three to run. I asked him, “Why don’t you simulate these on a computer? Not only will it allow you to run your experiments faster, but someday every freshman microbiology student in the country can play with the Paul Berg recombinant software.” So his eyes lit up. And that was sort of a landmark lunch. Because that’s when I started to really think about this stuff and get my wheels turning again.

On Becoming Majority Shareholder in Pixar

In 1996, the year after Pixar released Toy Story and held its IPO, Steve looked back on the work and ideas that first drew him to the company.

I met Ed Catmull, who was running the computer division of Lucasfilm, in 1985. […] I’d been involved in graphics most of my life. The Apple II, though most people don’t remember, was the first real color computer that you could get your hands on. The Macintosh, obviously, was graphics. The LaserWriter was graphics. But it was all 2-D. We’d done some 3-D work at Apple, and I was certainly aware of the field—but the stuff that Ed and his team were doing was way ahead of anything I’d ever seen anyone do.

On Pixar’s Early Days

In 2003, with Disney and Pixar deep in negotiations over the future of the studio, Steve told filmmaker Leslie Iwerks about Pixar’s start.

Our strategy in the early days of Pixar was: find a way to pay the bills. In the background, we were developing animation software, and John [Lasseter] was making the succession of short films on the way to Toy Story. But we were trying to pay the bills and just buy time. That strategy really turned out not to work. Probably if you look back in the rearview mirror, we would have been better off just funding the animation efforts and not trying to pay the bills through these other products, such as the Pixar Image Computer and software, but that was our best attempt to try to keep the company going. In the end, I just ended up writing checks to keep the company going—and that basically went on for ten years. ✂

You could see there was magic in [a Pixar animated short film], right from the beginning. With the rest of Pixar’s technology, you had to be an expert to understand it. [… But] you didn’t have to know anything about the technology to enjoy the film. It was incredibly refreshing and really pointed the way to where we wanted to go. We didn’t want to have to convince people that our technology was great—we knew it was great. We wanted to use our technology to make something where nobody needed to know anything about the technology to love it. And that’s what we ended up doing.

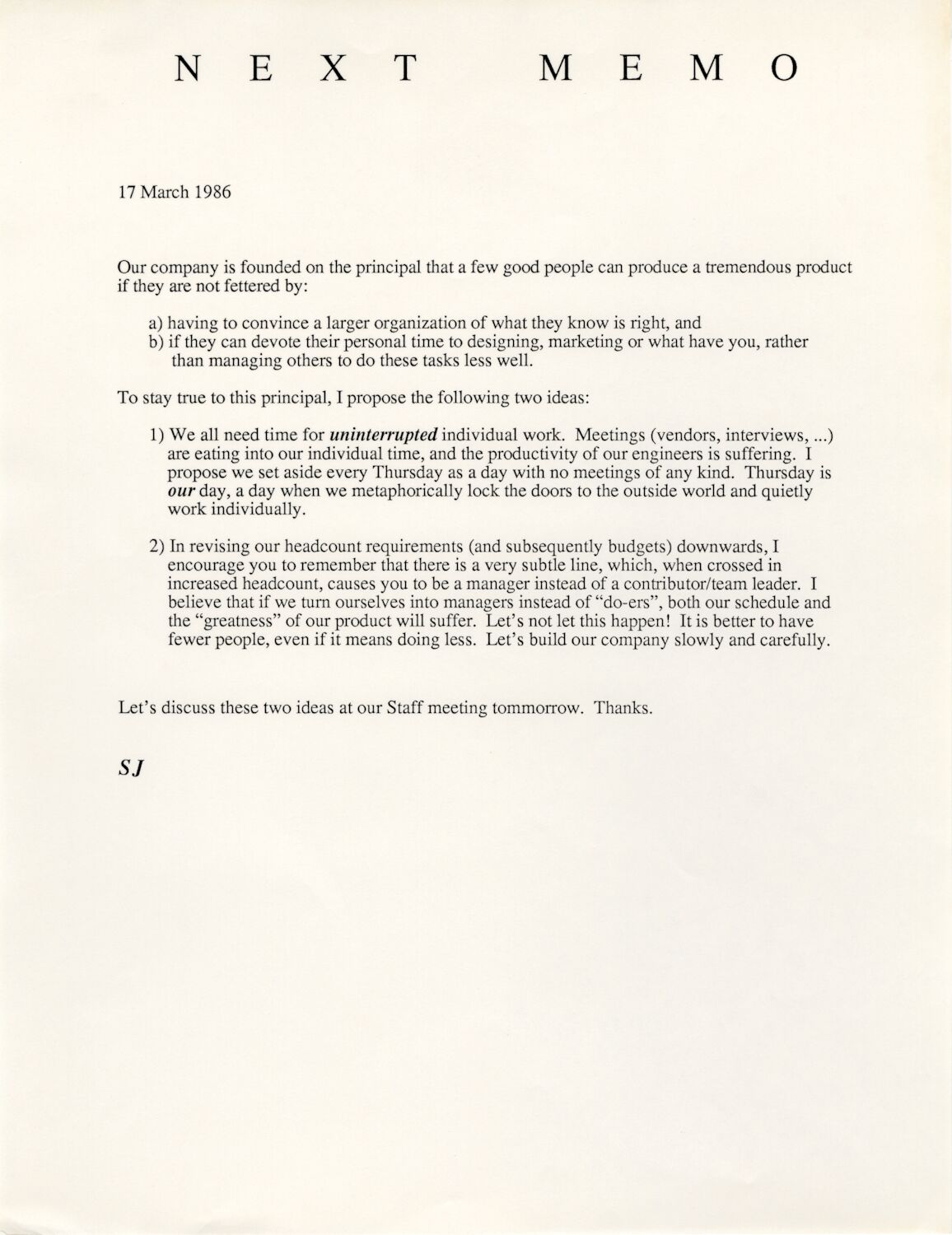

Email to NeXT Employees

“Pixar led the way!”

From: Steve Jobs

To: NeXT

Subject: A great day and a half

Date: March 30, 1989, 8:08 p.m.

Well, we did it again. Congrats to all for a real TEAM effort. And, Pixar did it too.

For those of you who didn’t see the Academy Awards last night, Pixar won an award in the category of short animated films: for their computer generated film Tin Toy

Tin Toy is the first computer generated film to ever win an award, and was competing against several very good traditionally animated (non-computer-animated) films!

The computer graphics industry just achieved a major milestone, and Pixar led the way!

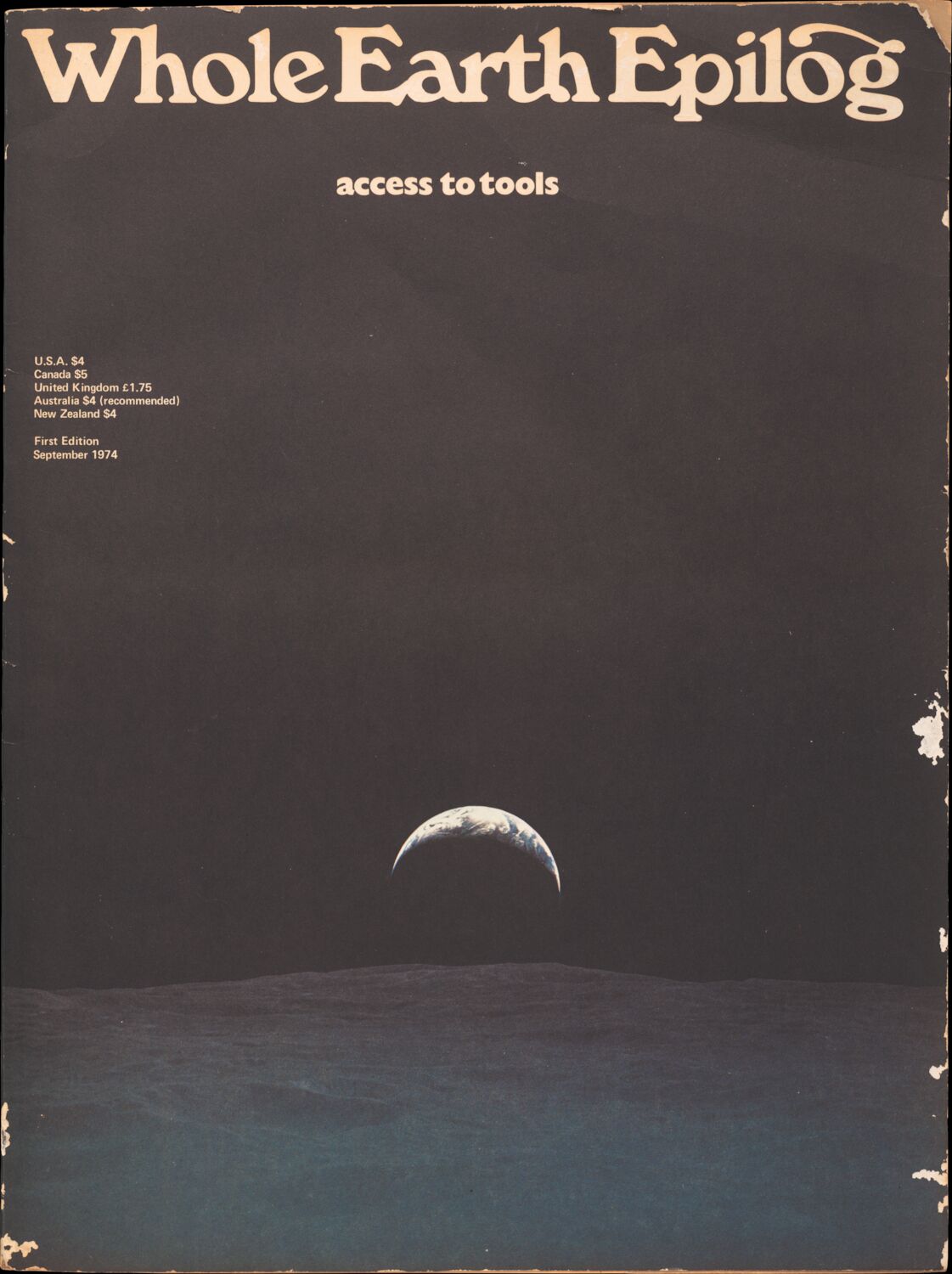

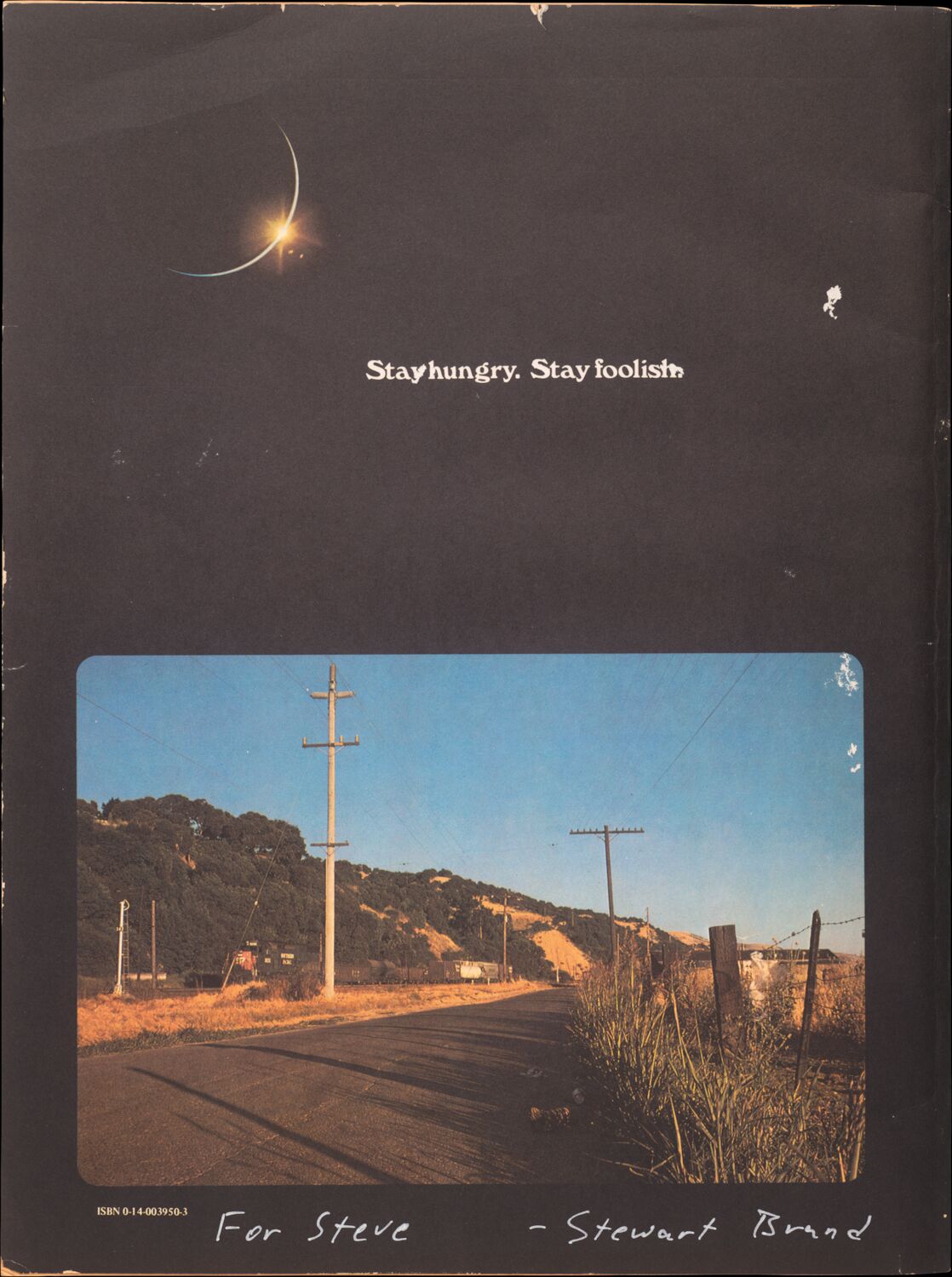

Speech at Reed College

“Character is built not in good times, but in bad times.”

When Steve welcomed the incoming class of freshmen at his alma mater, Reed College, on August 27, 1991, NeXT computers were not selling well and Pixar had just had a round of layoffs.

Thank you very much for this. It means a lot to me. I’m a peculiar Reed alumnus, as many of you know. I never graduated from Reed—although that doesn’t make me that unusual, I suppose.

But maybe more unusual: I ran out of money after one semester here at Reed, so I dropped out. But then I dropped in for another year and a half. So, I was actually here by choice, which is somewhat more unusual. And I had some experiences here—that I’m sure many of you will have as freshmen and throughout your years here—that have stayed with me my whole life. I was thinking of some of them to recount to you.

Remember that I’m much older than you now. I’ve always thought that people’s spark of self-consciousness turns on at about fifteen or sixteen. So if we normalize age to fifteen or sixteen, then most of you are two or three or four years old here, as freshmen. I’m about twenty. So that maybe puts in perspective what it’s like to return to Reed after so many years. But a few things stick in my mind that I wanted to pass on that maybe could be of some value. The first was that, as you will be shortly, I was forced to go to humanities lectures—it seemed like every day. I studied Shakespeare with Professor Svitavsky. And at the time, I thought these were meaningless and even somewhat cruel endeavors to be put through. I can assure you that as the patina of time takes its toll, I thank God that I had these experiences here. It has helped me in everything I’ve ever done, although I wouldn’t have ever guessed it at the time.

The second experience that I remember from Reed is being hungry. All the time. The cafeteria here taught me quickly to be a vegetarian. I didn’t have so much money, so I would gather up Coke bottles and take them up to the store to find out how to eat. I discovered the cheapest way to eat was Roman Meal. Have you ever heard of this? It’s cereal. It was invented by a Harvard professor who was a history professor who one day wondered what the Roman legion took with them to eat as they conquered and pillaged these villages, and he found out through his research that it’s Roman Meal. And you can buy it at the local store, and it’s the cheapest way to live. So I lived for many months on Roman Meal.

But also, several of us, after not eating for a few days, would hitchhike across town to the Hare Krishna temple on Sundays, where they would feed all comers. Through practice, we discovered just the right moment to arrive—after their particular religious practices and right before the food. And not having eaten for days, we would eat a lot, and on several occasions stay over, because we were not able to move.

The following morning, they would wake us up at four o’clock in the morning because it was their time to go gather flowers for their temple to honor Krishna. So they would take us with them, predawn, out into the neighborhood—where they would proceed to steal flowers from the neighbors. And the neighbors that lived close to the Hare Krishna temple soon were wise to their pillage and would get up early in the morning and guard their flower beds. And so they would have to go in an ever-wider circumference around their temple. In spending a little time with these people, I noticed some of their other behaviors. They used to sell incense to the local department stores and then go steal it back, so that the department stores would buy more, and they would have a thriving business. And their ethics told them that this was fine, that anything in the service of Krishna was fine. In interacting with them, I think I learned more about situational ethics than I ever did on campus.

The last experience I wanted to recount for you: there is a man—I think he’s here today—named Jack Dudman, who used to be the dean of the school. He was one of the heroes of my life while I was here, because Jack Dudman looked the other way when I was staying on campus without paying. He looked the other way when I was taking classes without being a formal student and paying the tuition. And oftentimes, when I was at the end of my rope, Jack would go for a walk with me, and I would discover a twenty-dollar bill in my tattered coat pocket after that walk, with no mention of it from Jack before, during, or after.

I learned more about generosity from Jack Dudman and the people here at this school than I learned anywhere else in my life. So I wanted to thank this community, because the things I learned here stayed with me. Character is built not in good times, but in bad times; not in a time of plenty, but in a time of adversity—and this school seems to manage to nurture that spirit of adversity, and I think does build some character. So I thank you for teaching me how to be hungry and how to keep that with me my whole life.

Thank you very much.

Email Exchange Between Steve, Intel CEO Andy Grove, and an Intel Engineer

“I have changed my position 180 degrees.”

As Pixar became a leader in graphics, Steve and his mentor, Intel CEO Andy Grove, discussed how Intel might learn from Pixar. When an Intel engineer tried to follow up, Steve resisted.

From: [Engineer 1 at Intel]

To: Steve Jobs

Cc: Andy Grove

Subject: Pixar-3D graphics

Date: September 22, 1995, 2:04 p.m.

Steve,

Andy asked me to look into what we should do in dramatically improving the Intel architecture platform’s 3D graphics performance. He indicated that you and key people at Pixar like Ed Catmull have lots of good ideas on what we should do in this area. I actually contacted Ed several months ago but he was real busy and cannot commit to meeting until after Sept. As you know, I am in charge of microprocessors at Intel.

I have located several key Intel 3D experts. One of them, [Engineer 2], came from Sun over a year ago. I would like to have a meeting (at Next, Intel or Pixar) with you, Catmull, and others with me and our graphics experts to discuss your ideas and map out what our action plans are. I am in Tokyo next week but will be back in my office on Monday Oct. 2. I will ask my admin to contact your office to set that meeting up.

Thanks.

[Engineer 1]

From: Steve Jobs

To: [Engineer 1]

Subject: Pixar-3D graphics

Date: September 23, 1995, 7:11 p.m.

[Engineer 1],

Pixar does indeed possess the knowledge to enable Intel’s processors to render 3D graphics at much high performance and quality. These “secrets” could definitely make their way into future Intel general purpose processor hardware.

We believe this single capability is the key for Intel to dramatically enlarge the PCs market share in the consumer market – by significantly surpassing the dedicated gaming machines (Sega, Nintendo, Playstation, etc) graphics capabilities.

Pixar’s secrets were invented through significant investment over ten years or more, and we value them highly. Even without the secrets implemented in the processor, Pixar can gain significant competitive advantage and differentiation through implementing them in software. By disclosing the “correct” way to do high quality, high performance graphics, Pixar will lose much of this to any and all competitors, with no work on their part. Hence, the need for compensation.

What does Intel propose to give Pixar for disclosing and licensing its secrets to Intel?

Steve

From: [Engineer 1]

To: Steve Jobs

Cc: Andy Grove

Subject: Re: Pixar-3D graphics

Date: September 25, 1995, 11:22 a.m.

Steve,

We would very much like to have our meeting, but I will put that on hold based on your input. We talked to many key people on ideas to improve the microprocessor capability with the aim that this will benefit the whole industry, and everyone will benefit. We have not entered into any financial arrangement in exchange for good ideas for our microprocessors in the past and have no intention for the future.

[Engineer 1]

From: Steve Jobs

To: [Engineer 1]

Cc: Andy Grove

Subject: Re: Pixar-3D graphics

Date: September 25, 1995, 5:29 p.m.

This approach has not served you well in the past, as evidenced by your poor graphics architectures and performance. Maybe you should think of changing it for the future…

Steve

From: Steve Jobs

To: Andy Grove

Subject: Re: Pixar-3D graphics

Date: September 25, 1995, 10:27 p.m.

Andy,

Maybe it’s just me, but I find [Engineer 1]’s approach extremely arrogant, given Intel’s (his?) dismal showing in understanding computer graphics architectural issues in the past…

If I were going to make hundreds of millions of something, I sure as hell would be willing to pay for the best advice money could buy… Any[way], this isn’t a sales pitch; I just wanted you to know what I thought, as always.

Best,

Steve

From: Andy Grove

To: Steve Jobs

Subject: Re[2]: Pixar-3D graphics

Date: September 26, 1995, 3:12 p.m.

Steve,

I am firmly on [Engineer 1]’s side on this one. He is taking your offer to help us very seriously, rounded up the best technical people and was ready to go when you introduced a brand new element into the discussion: money.

You and I have talked many times about this subject; you never suggested or hinted at this being a commercial exchange. I took your offer to help us exactly as that: help, not an offer of a commercial relationship.

You may remember, that from time to time I offered suggestions that pertained to your business. Examples range from porting NextStep to the 486 - - which was in our interest too - - to my presentation to your staff on repositioning NextStep beyond that. I am not suggesting that these are comparable in value to your expertise in graphics, but I gave what I had, put some thought into the problem I saw you were facing - - and it never entered my mind to charge for it. In my view, that’s what friendly companies (and friends) do for each other. In the long run, these things balance out.

I am sorry you don’t feel that way. We will be worse off as a result, and so will the industry.

Regards,

a

From: Steve Jobs

To: Andy Grove

Subject: Re[2]: Pixar-3D graphics

Date: October 1, 1995, 3:50 p.m.

Andy,

I have many faults, but one of them is not ingratitude. And, I do agree with you that “In the long run, these things balance out.”

Therefore, I have changed my position 180 degrees - - we will freely help [Engineer 1] make his processors much better for 3D graphics. Please ask [Engineer 1] to call me, and we will arrange for a meeting as soon as the appropriate Pixar technical folks can be freed up from the film.

Thanks for the clearer perspective.

Steve

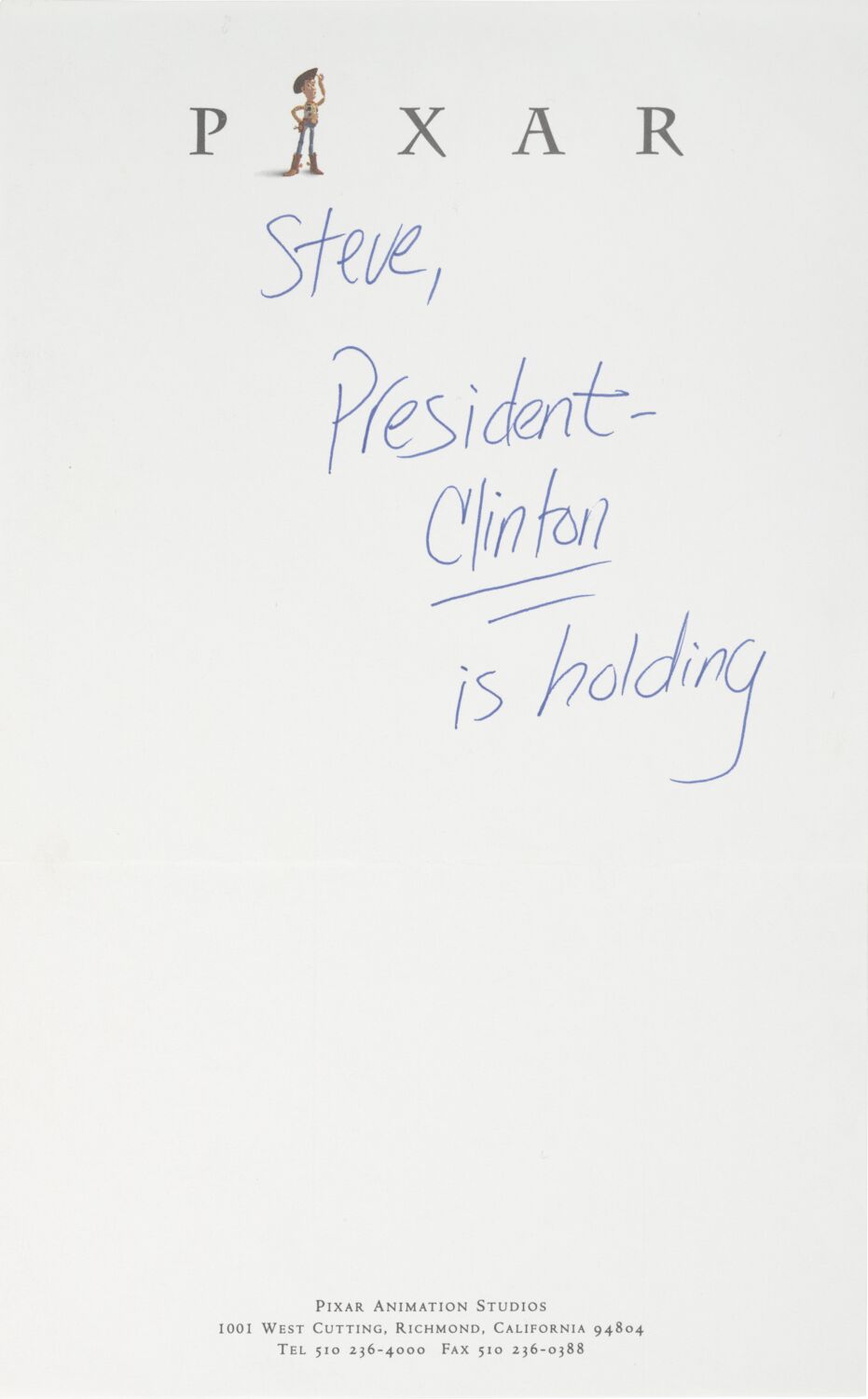

Email to Pixar Employees

“To $175M and beyond!”

From: Steve Jobs

To: Pixar

Subject: Toy Story Crosses $150M !!

Date: January 2, 1996, 9:30 a.m.

Yesterday Toy Story crossed $150M in domestic box office receipts -- only 13 days after crossing $100M !!

Toy Story was the undisputed blockbuster of the holiday season, topping all other films including Jumanji, Father of the Bride II, Waiting to Exhale and, of course, Balto. Toy Story may even surpass the current 1995 box office leaders, Batman Forever ($184M) and Apollo 13 ($172M), and become the most successful film of 1995.

Toy Story has already become the third most successful animated feature film of all time, topping all of Disney’s classics except “Aladdin” ($217M) and “The Lion King” ($312M).

To $175M and beyond!

Congratulations team,

Steve

Interview with Terry Gross

“One of the things I always tried to coach myself on was not being afraid to fail.”

In 1996, Steve and the Fresh Air radio host Terry Gross looked back on his time at Apple and ahead to the future of the computer industry. They spoke shortly after Pixar’s release of Toy Story and its successful initial public offering. NeXT, meanwhile, continued to struggle.

Terry Gross: How do you think that the web might change in the near future with the help of the type of software that you are producing now?

Steve Jobs: I think most large companies and medium-size companies (and even small companies) are starting to look at the web as the ultimate direct-to-customer distribution chain, bypassing all middlemen, going directly from the supplier to the consumer. That’s a pretty powerful concept when you think about it. One of the things that I love is that a very small company, if they invest a lot in their website, can look just as formidable and just as solid on the web as a very large company can. As a matter of fact, some of the smaller companies are more hip on the web, getting more hip to the web sooner, and so they actually look better than some of the large companies do right now. It’s going to be this very leveling phenomenon, but I think a tremendous amount of goods and services is going to be sold, or at least the demand created for such things, over the web.

TG: What else do you see in the near future for the web, besides the ability to shop in a more kind of complete way through the web?

SJ: It’s not just shopping for goods and services. It’s shopping for information. I mean, you’re going to find out … Already, when I want to find out the movies that are playing around Silicon Valley, I just go up on the local web page and check it out. It’s a lot faster than going through the newspaper, and a lot faster than calling the theaters, et cetera. More and more, we’re shopping for information on the web. I just recently bought a Sony, one of the new Sony camcorders. I went on Sony’s web page, and I found out all about the ones they offer and picked the one I wanted right from that web page before I even called the store to try to find it physically. The demand to get me to buy that thing was created from Sony’s web page. I think we’re going to see more and more of that. You’re going to be buying information or finding information, and really making a lot of decisions about what you’re going to do with your life, or what you’re going to purchase, from the web.

TG: Is the whole idea of going to the store to buy software going to become obsolete, too? Do you think we’ll be downloading our software from the web?

SJ: Of course. Yeah, there’s no question about it. There’s no question that that will happen, and I think it will happen in the next twenty-four months. There’s some software right now that’s still very large. The web on-ramps and off-ramps to corporations are now very fast, but the off-ramps to the consumers’ homes are still not so fast. For buying large software, such as CD-ROM games and stuff, they’ll still be distributed on physical media for a while, but when the off-ramps to the consumer get faster, possibly with cable modems in the near future, then that could possibly go fully electronic as well.

TG: Tell me what else you see for the web beyond the world of retail.

SJ: There’s a lot of things happening with the web right now, in terms of allowing people access to information that they would just never have before. What this does is, of course, it lets special-interest groups get together. I know people who have had, as an example, a stroke, and have gotten on the web and found that there are several web pages now devoted to information for stroke victims where they can learn about some of the latest treatments. They can learn about avoidance, the latest in avoidance advice, and things like that. Those things didn’t exist before, as well. ✂

TG: Do you think that when you were ousted from Apple that people kind of wrote you off? I mean, here you are with these big successes now.

SJ: Oh golly, I don’t know. I’m sure that a lot of people did, and that was fine. It was a very painful time, as you might imagine.

TG: What, to be forced out of the company you created?

SJ: Oh, of course. That was a very painful time, but you just march forward, and you try to learn from it. One of the things I always tried to coach myself on was not being afraid to fail. When you have something that doesn’t work out, a lot of times, people’s reaction is to get very protective about never wanting to fall on their face again. I think that’s a big mistake, because you never achieve what you want without falling on your face a few times in the process of getting there. I’ve tried to not be afraid to fail, and, matter of fact, I’ve failed quite a bit since leaving Apple.

TG: Are you surprised at the problems Apple is having now, or did you see that coming?

SJ: I try not to talk about Apple too much. What I will say is that the day I left Apple, we had a ten-year lead over Microsoft. In the technology business, a ten-year lead is really hard to come by. It happens, maybe a company has that once every few decades, whether it be Xerox or IBM with mainframes. Apple had that with the graphical user interface. The problem at Apple was that they stopped innovating. If you look at the Mac that ships today, it’s 25 percent different than the day I left, and that’s not enough for ten years and billions of dollars in R&D.

It wasn’t that Microsoft was so brilliant or clever in copying the Mac. It’s that the Mac was a sitting duck for ten years. That’s Apple’s problem, is that their differentiation evaporated. Unlike Compaq, or others who play in the Intel-Microsoft standard space, where they only … Compaq only has to be 5 percent better than its competitors for everyone to want to buy their computers.

Apple has to be 50 percent or 100 percent better, because when you buy something that is out of the mainstream a little bit, you take a risk, and you want a much bigger reward for taking that risk. […] That differentiation has not completely evaporated, but for the most part it has. That’s the predicament Apple’s in now. That’s why cost-cutting and other things at Apple are not going to be the cure. The cure for Apple is to innovate its way out of its current predicament. There’s a lot of good people left at Apple that are capable of doing that with the proper leadership, which is what’s been missing.

TG: Some Mac users are afraid that the Mac operating system is in danger of becoming obsolete in the way that Beta video became obsolete because it was outdone by VHS. What do you think?

SJ: I think with the appropriate leadership at Apple, that’s not going to happen, but I think we have to wait and see.

TG: Do you care? How still involved, invested, do you feel in the future of Apple, the company you co-created?

SJ: I’m happy every time a Mac gets shipped. I still have people sending me emails, telling me how much they love their Macs. It’s sort of … how do you explain it? It’s like the first person you were ever in love with. You know? It’s like your first love, and there will never be another one like it. In my case, we were together for ten years, and that’s a long time. But if you move on in your life, you can’t always stay in love with your first girlfriend. Right? ✂

TG: What do you think the state of the computer would be if it weren’t for Apple? This is a chance, I guess, for a really self-serving answer. But, I mean, I’m really curious what you think.

SJ: I usually believe that if one group of people didn’t do something, within a certain number of years, the times would produce another group of people that would accomplish similar things. We happened to be at the right place, at exactly the right time, with the right group of people. We did some wonderful work. I’m extraordinarily proud of the work that the team at Apple did when I was there. I think that, personally, our major contribution was a little different than some people might think. I think our major contribution was in bringing a liberal arts point of view to the use of computers.

TG: Yeah, explain what you mean by that.

SJ: What I mean by that is that if you really look at the ease of use of the Macintosh, the driving motivation behind that was to bring—not only ease of use to people so that many, many more people could use computers for nontraditional things at that time—but it was to bring beautiful fonts and typography to people. It was to bring graphics to people, not for plotting laminar flow calculations, but so that they could see beautiful photographs, or pictures, or artwork, et cetera, to help them communicate what they were doing, potentially. Our goal was to bring a liberal arts perspective and a liberal arts audience to what had traditionally been a very geeky technology and a very geeky audience.

TG: What made you think that that more liberal arts direction was the direction to head in?

SJ: Because in my perspective, and the way I was raised, was that science and computer science is a liberal art. It’s something that everyone should know how to use, at least, and harness in their life. It’s not something that should be relegated to 5 percent of the population over in the corner. It’s something that everybody should be exposed to, everyone should have a mastery of, to some extent, and that’s how we viewed computation, or these computation devices.

TG: And you think that concept really caught on in the whole industry, eventually?

SJ: That’s the seed of Apple: computers for the rest of us. I think the liberal arts point of view still lives at Apple. I’m not so sure that it lives that many other places. I mean, one of the reasons I think Microsoft took ten years to copy the Mac was because they didn’t really get it at its core.

TG: Do you think the PC, as we know it, is on the road of changing?

SJ: That’s a really big question. I think the PC as we know it is going to be around for quite some time, but the heart of the question is, are we entering a time window where we might see the first successful post-PC devices? Personal digital assistants, or PDAs, attempted to be that and failed.